Pediatric Inguinal Hernia and Hydrocele

→ Enlace a la versión en español

History

Inguinal hernia remains one of the most common surgical disorders in children. Literature for inguinal hernia has spanned more than 20 centuries and with new techniques there have been new insights into management as well. Inguinal hernia is a perfect example of a disorder where seemingly a lot has changed whereas in effect nothing much has changed. As medical students it is often the first surgical disorder to be demonstrated in ward rounds and which we learn to examine and diagnose.

Galen in 176 A.D was the first one to describe the pathogenesis of indirect inguinal hernia when he described the processus vaginalis as “The duct descending to the testicle is a small offshoot of the great peritoneal sac in the lower abdomen (processus vaginalis peritonei) [1, Singer, 1956]. First documented surgical therapy for inguinal hernia was in 5th century A.D. by Susruta from India- also referred to as Father of Indian Surgery [2]. An accurate description of inguinal canal anatomy preceded the first successful repair in early 19th century. Contributions received from Camper, Cooper, Hesselbach and Scarpa laid the foundations for Bassini and Halsted to propose sound anatomical repairs [3-8]. Further results were enhanced by promulgation of antiseptic techniques by Lister which allowed surgeons to proceed with surgery without worries of wound infection, which was then the bane of all surgical procedures [9].

Ferguson proposed hernia repair by just exposure, dissection, simple high ligation and removal of the hernia sac, and this was applied successfully to the pediatric population by Potts et al [10,11]. While in adult hernia repairs, the underlying principle involved reconstruction of weakened muscles and aponeurosis in multiple anatomical layers, for pediatric hernia simple dissection and high ligation of processus at internal ring was found to be sufficient to provide a long lasting cure to repair indirect inguinal hernia. The Ferguson principle sans the excision of hernia sac still is the basis of all pediatric hernia repairs even in the 21st century. With advances in operating room asepsis, better suture materials and pediatric anesthesia almost all the indirect hernia repairs have become day surgery procedures.

Pathogenesis

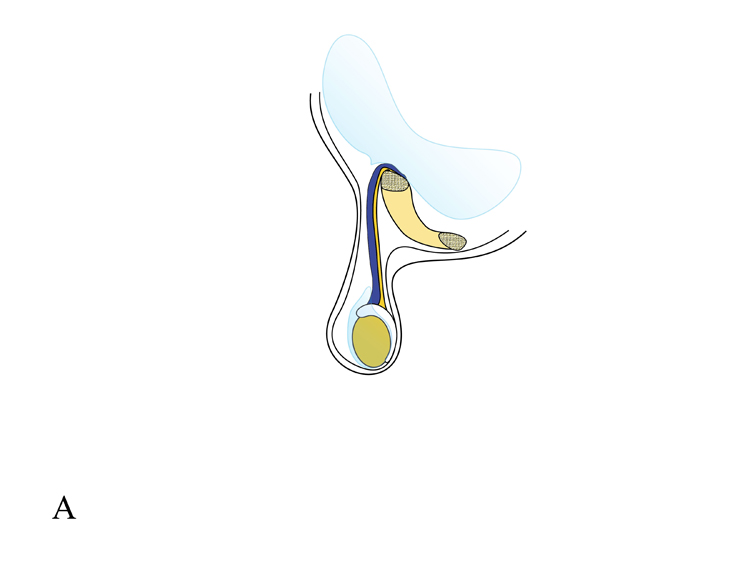

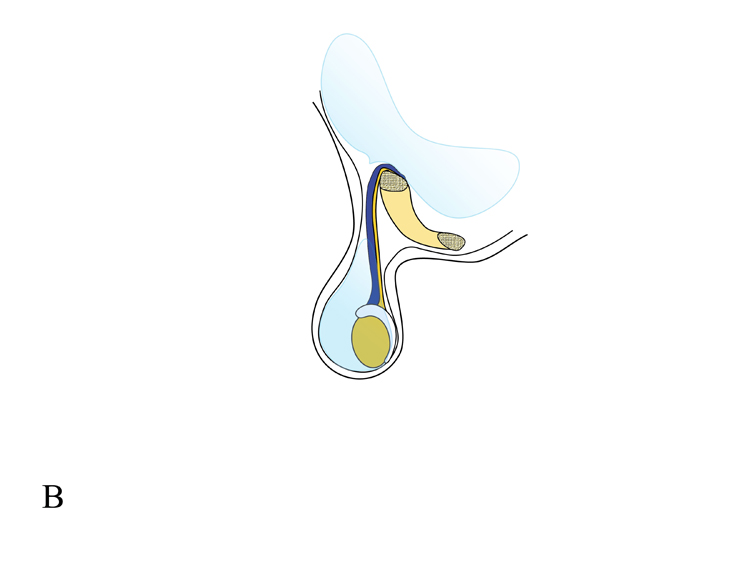

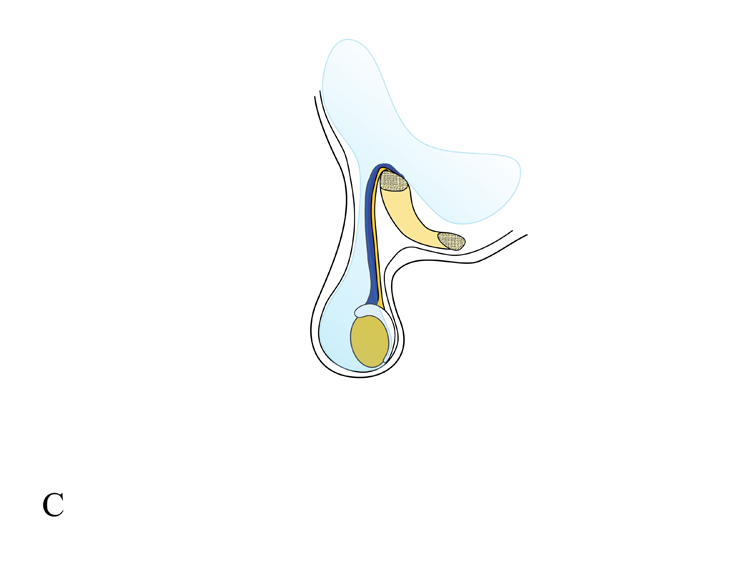

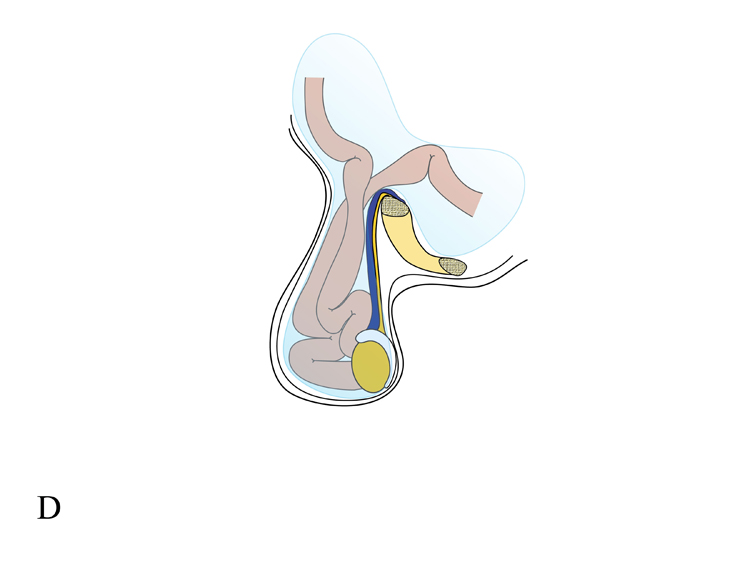

Inguinal hernia and various types of hydrocele in children result from a patent processus vaginalis which has failed to obliterate after the descent of testis through it (Figure 1).

B: Collection of fluid around testis in tunical vaginalis constitutes scrotal hydrocele

C: Communicating hydrocele exists when the processus vaginalis is patent through inguinal

D: Herniation of bowel loops into scrotum in an inguinal hernia.

(Illustrations by Dr Paul Gleich, M.D.)

In contrast to acquired weakness leading to hernias in adults, indirect inguinal hernias in children result from an arrest of embryologic development and this also explains the increased incidence in premature infants. The formation of inguinal hernias in children is directly linked to descent of the developing gonads. In the developing fetus, the processus vaginalis is first seen as an outpouching of the peritoneal cavity in the third month of gestation. Testes develop in the embryologic retroperitoneum near the kidney and come to lie at the level of the internal ring in the seventh month. The processus vaginalis extends across the inguinal canal into the scrotum and provides the necessary pathway for the testis to make its way into scrotum. Once this pathway is laid, a well orchestrated sequence of events allows the testis to descend to the scrotum [12]. Shortly after descent of testis, sometime in the first few months of life, most of the processus gradually obliterates except the terminal portion around testis which persists as the tunica vaginalis. The tunica normally contains a small amount of fluid and invests the testis on almost all sides in the scrotum forming an important covering and a protective layer for the testis. Hydrocele and hernia occurs as a variation of this theme itself whereby a part of processus vaginalis remains behind. The calibre of the patent processus determines whether a hernia or a hydrocele will manifest. A small calibre channel allows only peritoneal fluid to seep through leading to a communicating hydrocele, while a larger defect allows intra-abdominal viscera to migrate manifesting as an inguinal hernia.

The precise timing of spontaneous closure of the processus is not known in the normal population as most of the studies concerning the rates of patencies at various ages in childhood have been done at the time of contralateral open or laparoscopic visualisation during routine hernia repair. According to variable data, 40% of the patent processus vaginalis close during first few months of life and an additional 20% close by 2 years of age [13, 14]. As the left testis descends before the right, the right processus closes later explaining the higher incidence of hernias and patent processus on the right side. A patent processus has been recognised more and more often with evolution of laparoscopic techniques for pediatric hernia repairs and has been theorised to be a potential area for development for hernia [14].

The presence of a patent processus vaginalis is a necessary but not sufficient variable in developing a congenital indirect inguinal hernia. Put in another way, all congenital indirect inguinal hernias are preceded by a patent processus vaginalis, but not all patent processus vaginalis go on to become inguinal hernias. In recent studies on adults with indirect hernias, the contralateral processus has been found to be patent in 12-14%, and further, in those with patent rings only 12-14% have been shown to develop contralateral hernias [15, 16]. Because the overall incidence of indirect inguinal hernias in the population is approximately 1% to 2% and the incidence of a patent processus vaginalis is approximately 12% to 14%, clinically appreciable inguinal hernias should develop in approximately 8% to 12% of patients with a patent processus vaginalis [17]. These data imply that all open internal rings and patent processuses do not lead to clinical hernia. There may be other factors which may influence the development of clinically evident hernia

HERNIAS

Epidemiology

Incidence, Age, Sex, Side, Family History

Inguinal hernia is one of the common disorders in childhood and has been documented to occur in 0.8-4.4% of the children; the incidence is higher in neonates and infants [18,19]. The incidence of pediatric inguinal hernia is highest during the first year of life and then gradually decreases thereafter. One-third of children undergoing surgery for hernia are less than 6 months of age [15]. Premature infants have an even higher risk of developing inguinal hernia with reports of incidence of upto 25% [20-22].

Incidence of hernia is 6 times more in boys than girls, and the sex ratio has been reported to be variously from 3:1 to 10:1 [23]. This is possibly related to descent of testis through the inguinal canals in males.

Hernias are more common on right side with 60% occurring on the right side, 30% on left side and 10% are bilateral. This distribution does not change with sex as even in girls a right side predominance is seen [23].

Increased incidence of inguinal hernia has been documented in the second twin once the first one has been diagnosed to have a hernia. Sisters of an affected girl have the highest relative risk of 17% while for other siblings, the risk is 4-5% [24]. Also, there may be a history of inguinal hernia in another member of the family in 11.5% of the cases [18,24,25].

Risk Factors for hernia:

Table 1:

Table 1: Risk factors for increased incidence of hernia in children

Urogenital |

Undescended testis |

|

Exstrophy of bladder |

|

|

Increased peritoneal fluid |

Ascites |

|

Presence of Ventriculoperitoneal shunt |

|

Peritoneal dialysis |

|

|

Increased intra-abdominal pressure |

Repair of gastroschisis/ exomphalos |

|

Severe ascites- liver failure, chylous etc |

|

Meconium peritonitis |

|

|

Chronic respiratory disease |

Cystic fibrosis |

|

|

Connective tissue disorders |

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome |

|

Hunter- Hurler syndrome |

|

Marfan syndrome |

|

Mucopolysaccharidosis |

|

|

Miscellaneous |

Developmental dysplasia of hip |

|

|

|

|

Clinical Features

Symptoms

Inguinal hernia is suspected when a child is noticed to have a swelling in inguinal area or scrotal area (Figure 2). Classically, the hernia swelling is intermittent in nature, appearing only when intra-abdominal pressure rises, forcing intra-abdominal contents down the inguinal canal. Commonly this occurs when the child is coughing, playing or crying. At this stage the hernia is reducible and there are no other symptoms. Occasionally, in a large hernia, there may be some dragging sensation or mild heaviness in the scrotal or inguinal area. Significant pain signifies onset of complications such as incarceration or strangulation.

Examination

Examination for hernia requires patience and involvement to keep the small child engaged. It is a good practice to establish a rapport and not to hurry for the examination. Hands should be warm and the ambient temperature in the room should not be too low so as to prevent shivering and discomfort. Clinically, in a child with an evident hernia a smooth soft mass would be seen emerging from external ring which lies cephalad and lateral to pubic tubercle. This mass would be seen to enlarge when the child strains, cries or coughs. In case of an uncooperative child or preverbal age, straining can induced, by one of the many techniques to elicit hernia. The most common method is to try to straighten the legs as this causes the baby to strain and may result in hernia becoming evident.

Many a times a hernia is suspected on basis of history but cannot be demonstrated on examination in the outpatient setting. If the history is classical and referring pediatrician/ physician has seen the swelling and confirmed it to be a hernia, then surgery can be recommended. In case of any doubt, it may be wise to call for a second visit or ask the pediatrician/ physician to confirm whenever possible. Another diagnostic aid is the so called “Silk Glove Sign.” Silk glove sign refers to thickening and silkiness of the spermatic cord which can be palpated as the cord crosses the pubic tubercle [26]. This indicates presence of hernia sac around the cord and is a reliable sign especially in a unilateral hernia where the difference between the two sides may be easy to appreciate. A recent study has documented 91% sensitivity and more than 97% specificity for silk glove sign to predict presence of hernia [27].

On relaxing, the hernia swelling may disappear or become less prominent or it can be gently reduced by superolateral pressure towards the internal ring. Sometimes a retractile testis may lie near the external ring or even in the inguinal canal giving rise to a bulge in the inguinal region which can be mistaken for a hernia. Therefore, one must ascertain the position of testis before beginning examination for hernia. If the testis is retractile, then it should be brought into scrotum and then only hernia examination should be begun. Secondly, hernias are a part and parcel of the spectrum of undescended testis and if the testis is undescended, then orchiopexy will be required concomitantly.

Another tool to increase the diagnostic accuracy is use of office ultrasound in doubtful cases [28-31]. Ultrasound has been shown to differentiate between patent processus and a hernia reliably in some recent studies. Based on pre-operative and operative findings in more than 600 children with inguinal hernias who underwent pre-operative ultrasound, Erez et al reported that a hypoechoic structure in the inguinal canal measuring more than 6 mm indicates a hernia while between 4-5 mm indicates a patent processus vaginalis [29].

A recent study has explored the use of a suggestive history and digital photographs taken at home if the hernia is not clinically demonstrable in clinic [32]. Parents were asked to send in digital photographs if the history was suggestive of an inguinal hernia and children were operated if the photograph was unequivocal. All the children thus operated were confirmed to have an inguinal hernia intra-operatively. Though the study was a small one (23 patients), further consideration in the context of today’s digital world is reasonable.

Inguinal Hernia in Girls

Inguinal hernia predominantly occurs in males, as girls comprise less than 10% of all reported cases [33]. Clinically, the child would be brought with a history of inguinal swelling appearing on coughing or crying (Figure 3). Whenever a hernia is suspected in a girl, it is important to be aware of a potential disorder of sexual differentiation. Upto 1-2% of all female children with hernia would be found to have Androgen insensitivity syndrome [34-36]. In such a circumstance, a testis may be palpable in the inguinal region. In a girl with inguinal hernia, investigations should be done to rule out Androgen Insensitivity syndrome if there is any suspicion. Though the incidence is very low, it may have important medicolegal consequences if CAIS is discovered during surgery and has not been mentioned pre-operatively [34]. But given the low incidence, it is important to proceed with investigations thoroughly. The various investigations include ultrasound and karyotype. Routine screening with karyotype, though most specific may not be feasible for economic and technical reasons except when the hernia sac contains palpable gonads. In girls with only a hernia without a palpable gonad, ultrasound examination from a trained radiologist may be an adequate screening tool. Unequivocal visualisation of ovaries with follicles conclusively rules out Androgen insensitivity syndrome. Only in cases where ovaries are not visualised, karyotype may be required. Another adjunctive tool can be measurement of vaginal length in girls with hernias as children with androgen insensitivity syndrome have a shorter vaginal length [35, 36].

Commonly, the contents of the hernia sac are omentum and/ or small bowel. In girls, ovaries have a propensity to herniate into the sac and undergo incarceration (Figures 4, 5). If torsion sets in, this may lead to rapid infarction. Once diagnosed to have an ovary in the sac, surgery should be performed as early as possible to prevent such an eventuality [33, 37, 38]. Sliding hernias are also known to occur in children where part of the bladder wall or fallopian tubes/ uterus have been found in the hernia defect [33, 37, 38].

SURGICAL PROCEDURE

Though Ferguson and Czerny were the first ones to describe high ligation of the sac in pediatric patients, the classic contemporary description of the repair of indirect inguinal hernias in children was provided by Potts [10,11]]. High ligation of the sac is a technique which is practiced globally by all pediatric surgeons and urologists. With time, only minor changes have occurred, but the basic technique is directly descended from the procedure taught by Ladd and Gross, the founders of North American pediatric surgery [39].

With the advent of Laparoscopic techniques, multiple series have validated the feasibility and safety of laparoscopic approach for pediatric hernia repair, though the actual benefit over conventional open approach still remains debatable except in certain special circumstances.

Conventional Open approach

Surgery for hydrocele and hernia in children is classically performed via inguinal or groin crease incision. Inguinal herniotomy is a simple and precise surgery which can be performed expeditiously provided anatomical orientation is good and a layer by layer exposure of the structures is completed. Herniotomy can be performed under caudal epidural analgesia along with sedation or under inhalational anesthesia with a laryngeal mask airway. The child is placed in a supine position on the table and parts are prepped with an iodophor solution from epigastrium to midthigh level. The surgeon stands on the side of hydrocele/ hernia. Lower inguinal skin crease incision is marked centred over the pulsations of the femoral artery, over the expected internal ring (Figure 6). An incision is made through the dermis until the fatty layer of the superficial fascia is encountered. In this plane there is a constant vein which needs to be coagulated as this vessel may be a source of minor bleeding if not recognised early on. Then membranous layer of the superficial fascia (Scarpa’s fascia) is divided with cutting diathermy and this exposes the external oblique fascia. A small nick is given in the fascia and this fascia is divided with a fine scissors along the length of the incision. The edges of the inferior leaf may be held with fine haemostats and everted; this maneuver opens up the inguinal canal. Genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve is recognised coursing along the inferior leaf and this is gently retracted and protected. Caudal and medial traction is exerted with small fingertip retractors to expose the course of the spermatic cord. Cremaster fascia is gently separated to reveal the glistening white processus or hernia sac and this is held with a hemostat. In case of any difficulty in recognising the cord, a gentle to and fro pull on the testis will help in delineating the sac better. The sac once held, is lifted out of the incision and this should be easy to lift out. If this step is difficult, reassess the anatomy as it may be some other tissue or some more separation from the surrounding tissues may be required. Sac is splayed on the index finger of the left hand and tissues are teased off gradually layer by layer with an atraumatic forceps (Figures 7, 8) This way the spermatic cord with vessels and vas deferens are separated from the sac. It is vital not to handle vas during this maneuver as it can be injured very easily (vide infra). Once the sac is totally dissected clear of the cord, two hemostats are applied and the sac is divided in between (Figure 9). It is a good idea to confirm once again before applying the hemostats that no spermatic cord structure is caught in the sac tissue. After division of the sac, a gentle traction is kept on the proximal sac by the surgeon and the spermatic chord is gently held with the help of a gauze piece by the assistant. This allows splaying of the tissues between the sac and chord so that they can be bluntly pushed away with an atraumatic forceps. This dissection is continued till internal ring area is reached. This endpoint is recognised by visualisation of the extraperitoneal fat or the inferior epigastric vessels. An inspection and palpation is done to confirm that the sac is empty; in case of any doubt the sac can be opened by removing the hemostat and looking inside (Figure 10). This maneuver should be routinely done for all females undergoing hernia repair to rule out prolapsed ovary/ fallopian tube and also to confirm the presence of round ligament (Figure 11). Any contents are replaced inside the peritoneal cavity and the sac may be longitudinally twisted for 2-3 turns (Figure 12). This allows narrowing of the neck and also provides a slightly tougher tissue for placing a transfixation suture. Caution must be exercised as the twist of the sac could evert a spermatic cord structure inadvertently. A transfixation suture is passed with a delayed absorbable suture such as polyglactin or Poliglecaprone to secure the neck of the sac at level of internal ring. Sac is sectioned about 0.5 cm distal to the transfixation suture; at this juncture if the dissection has been adequate, the tied sac would be seen to retract into the depth. Now the attention is paid to the distal sac which has been held with the hemostat. The distal sac is laid open with a bipolar diathermy for a short distance to decrease the incidence of post-operative hydrocele. Hemostasis is ensured and the cord and testis are reposited back to the scrotum by a gentle pull on the scrotal tissues. This is again an important step, otherwise the testis can get trapped in the healing process and result in an iatrogenic ascended testis.

Tissues are re-approximated in layers with absorbable sutures and skin is closed in a subcuticular fashion or a tissue adhesive can be used for approximation. Tissue adhesives remain popular, but two studies showing that tissue adhesives have no improved outcome, take more time to use and may have slightly more complication rate bear mention [40, 41]. Typically a single poliglecaprone suture on a cutting needle is sufficient for the whole surgery. A small gauze dressing or skin strips are placed at the end of the procedure.

Special circumstances

Hernias in Premature infants

The preterm babies pose a unique combination of operative and perioperative risks, which influence the basic algorithm for management. Inguinal hernias are more common in premature infants, are more frequently bilateral and are prone to undergo incarceration [19-22]. The recent literature suggests that the risk of incarceration may not be as great as previously thought. In one prospective study of 51 premature infants who were observed to watch the natural history of their patent processus vaginalis and hernias, only 1 (2%) experienced an incarceration [42]. The hernia sac in premature infants is more fragile than in older infants and children, and, not surprisingly, the recurrence rate and complication rate after repair are slightly higher [43]. In addition, premature infants have an added risk of postoperative apnea and bradycardia [44-47]. This risk decreases as the infant matures. Postoperative apnea in premature infants after inguinal hernia repair using current anesthetic techniques is much less common than previously reported. Risk factors appear to include infants with prior history of apneas, lower gestational age, lower birth weight, lower weight at time of surgery, and a complicated neonatal course such as intraventricular hemorrhage, patent ductus arteriosus, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and requirement for mechanical ventilation and supplemental oxygen after birth. Selective use of postoperative ICU monitoring for high-risk patients could result in significant resource and cost savings to the health care system [48]. Using regional anesthesia to limit or eliminate the need for general anesthesia is also a helpful advance.

Balancing the increased risk of incarceration against the risk of perioperative complications in premature infants has led to two distinct schools of thoughts: to repair the hernia before the infant is discharged from the hospital or wait until they reach enough maturity to decrease the risk of postoperative apnea [44-47]. Premature infants who have symptomatic hernias, who have hernias that are difficult to reduce or who have families without the means to quickly follow-up with the surgeon should undergo repair before discharge. Otherwise, there are no good data to suggest that early repair versus waiting is superior, and both options should be discussed with the family [17].

Infants

In infants, the inguinal canal length is very short and the internal ring and external ring just lie over each other. As a result, infant herniotomy can be performed through the external ring without actually opening the inguinal canal. A small incision just above and slightly lateral to pubic tubercle may suffice to expose the sac as it exits the external ring. From there on the procedure is essentially the same as for older kids.

Large internal ring

In children with a large sac and a wide open internal ring, sutures can be placed laterally on the edges of the internal ring to make it smaller after a high ligation of the sac has been done [49].

Herniotomy for girls

As discussed previously, it is important to open the sac and confirm the presence of round ligament and also rule out fallopian tube, uterus, ovary which may frequently prolapse into the sac in female children [33,37,38]. If there is no content, then the sac can be just ligated as usual. If there is a fallopian tube inside then it should be gently reposited back into the abdomen and sac ligated distal the tube. The sac can be inverted back into the abdomen and internal ring closed.

Incarcerated hernia

Classically, the child would present with painful and persistent inguinal swelling (Figure 13). There may be redness and tenderness on examination. Abdominal distension and signs of intestinal obstruction may set in if diagnosis is not made early. Unless there is clear peritonitis or bowel compromise, attempt should be made to manually reduce the incarcerated hernias by using a technique called taxis. In this technique, with the infant relaxed (using sedation if necessary), gentle inferolateral pressure is applied to the incarcerated hernia with some pressure from above to straighten the canal. Approximately 80% of incarcerated inguinal hernias can be reduced using this technique [50]. Because of the high rate of early recurrent incarceration, it is recommended to admit these children and then do the surgery 24 to 48 hours later after the edema has subsided. Any child with an incarcerated hernia that cannot be reduced must undergo immediate operative repair. It is important not to reduce the hernia under anesthesia before the incision in order to inspect the incarcerated bowel for evidence of strangulation. In girls, an incarcerated ovary may be present in the hernia sac. If reduction is unsuccessful, there is a risk of vascular compromise from ovarian torsion occurring in as many as 33% of cases. Immediate repair can prevent this complication and is recommended by multiple authorities [38,50, 51]. Lately, laparoscopic approach to incarcerated hernia has been recommended by various authors and is discussed later (vide infra).

COMPLICATIONS OF HERNIOTOMY

The classical open approach with high ligation of hernia sac has stood the test of time and is associated with a complication rate of less than 2% [52].

Bleeding due to severing of small veins in superficial fascia may be a minor trouble and is generally easy to control. Bleeding may also occur secondary to injury to one of the fragile veins in the pampiniform plexus and can be easily controlled by pressure or bipolar diathermy. Bleeding from the edges of distal sac may lead to post-operative haematocele; thus it is important to achieve hemostasis by coagulating the edges of distal sac with bipolar cautery. Only after an adequate hemostasis should the testis be replaced back into the scrotum.

Occurs in less than 2 % of the cases and can be prevented by meticulous asepsis and hemostasis in operation room [52].

Injury to Ilioinguinal nerve is a rare occurrence. This slender nerve runs through the inguinal canal and upon opening the leaf of external oblique aponeurosis just runs over the spermatic cord. Careful eversion of the edge along with the nerve will prevent damage.

Prepubertal vas deferens is a very delicate structure and is susceptible to injury during pediatric hernia repairs as it runs along the hernia sac often invested in soft tissue of the wall of the sac [52-59]. Fortunately, incidence is less than 2% [52, 53]. Vasal injury during pediatric hernia repairs though rare, has been documented to be the most common etiology for obstructive azoospermia later on in adulthood and also the most difficult to repair [56]. Open exploration is associated with an increased risk of infertility; as many as 40% of infertile males who had bilateral hernia repairs as children have bilateral obstruction of the vas deferens [58]. Two types of injuries may occur- ischemic injury or sectioning of the vas. Ischemic injury results in a long segment of vas becoming fibrosed and is difficult to recognise during surgery itself. Classically, patients present with obstructive azoospermia later on in life and may need repair. Second type of vasal injury - sectioning of the vas is very uncommon in experienced hands, though the risk is higher in giant hernias of infants. If such an injury is recognised, it should be documented and surgical repair tried after mid-puberty as pre-pubertal narrow vasal diameter does not permit successful repair till tanner stage 3 has passed [56]. Overall, vasal injuries during hernia repairs are associated with longer vasal defects, impaired blood supply and longer obstructive intervals frequently resulting in secondary epididymal obstruction [50]. Vas deferens injury can also result in sperm-agglutinating antibodies which influence fertility [53]. Even minor inadvertent pinching of the vas or stretching of the cord can result in injury, which also increases the risk of infertility [54, 55, 61]. This inadvertent injury may be more likely when there is no true hernia sac present because the vas is more exposed making a case against routine contralateral exploration in a unilateral hernia.

Vascular compromise of testis leading to atrophy occurs in less than 0-3% - 2% of all hernia repairs [52]. This mostly occurs due to injury/ spasm of testicular vessels.

After mobilisation of the testis and division of the processus vaginalis, there is a raw area created which may entrap the testis. To prevent this from happening it is vital to pull the testis down and reposition it into the scrotum.

Post-operative hydrocele is a common occurrence and represents the continuing secretion of fluid by the left over distal sac. Most of the times it is a minor collection and gets resorbed spontaneously over a period of 2-3 weeks. In large hernias, the incidence may be higher. Therefore, during herniotomy, it is important to lay the distal sac widely open [62]. This maneuver widens the neck and thus provides more surface area for the fluid to get resorbed and prevent hydrocele. Hemostasis should be achieved adequately with preferably bipolar current after the sac edges have been laid open.

Factors that may contribute to recurrence in open inguinal hernia repair in children include failure to ligate the sac high enough, inadvertent tearing of the sac (and its extension into the peritoneal cavity), an excessively dilated internal ring, injury to the floor of the canal (with subsequent development of a direct inguinal hernia), and the presence of co-morbid conditions (eg, collagen disorders, malnutrition, or pulmonary disease). The recurrence rate has been documented to be around 1-3% [52, 63, 64].

In 1950’s reports appeared about a high rate of contralateral hernias in children presenting with unilateral hernias and Rothenberg recommended ‘‘prophylactic’’ contralateral exploration in all children [65]. These reports became the basis for the recommendation that all children undergo a contralateral exploration when a unilateral hernia was diagnosed. It has become clear now that these ‘‘hernias’’ were often the patent processus vaginalis and that, had they been left alone, a majority of them may not have become clinically significant hernias. The debate about contralateral exploration involves a choice between treating only obvious hernias (and dealing with a metachronous hernia later) versus preventing metachronous hernias by closing any patent processus vaginalis that is found. Ein etal in one of the largest series of pediatric hernias reported only a 5% metachronous hernia rate in a follow-up as long as 35 years. Among the risk factors for developing metachronous contralateral hernias, age less than 18 months, initial left side and large hernia seem to be significant [66-68]. Still the risk is not high enough (less than 5% in most series) to mandate a routine contralateral exploration. After weighing the risks such as real possibility of vasal injury or testicular atrophy in the light of low risk of contralateral hernia, most surgeons now believe that routine open contralateral exploration is not indicated [66-70]. Even in preterm babies if there is a unilateral clinically evident hernia at presentation, contralateral exploration is no longer recommended. A close clinical follow-up is advisable though [71].

Laparoscopic Approach to Pediatric hernias

Although the classic open inguinal hernia repair remains the gold standard for most pediatric surgeons, laparoscopic repair is increasingly being performed in many centers across the world. Initial use of laparoscopy in pediatric inguinal hernia was for diagnostic purposes; primarily to determine contralateral patent processus vaginalis (CPPV) [72-82]. The diagnostic efficacy of laparoscopy has been enhanced further by the use of an ever-expanding range of probes, endoscopic retractors, needles, and other endoscopic instruments to explore the patency in doubtful cases. Of these, the transinguinal approach with a 120 degree scope has been the most favored as a diagnostic tool [82]. With a sensitivity of 99.4% and specificity of 99.5%, laparoscopy has proved to be the gold standard for the detection of CPPV [78-82]. After the initial enthusiasm in detecting CPPV and repair thereof, recently many reports have challenged its validity as CPPV may not manifest into a clinical hernia later [70]. In other words, diagnosing a patent processus and treating it, is not analogous to treating a hernia.

Therapeutic use of Laparoscopy in pediatric inguinal hernia was first reported by El-Gohary in 1997 when he performed laparoscopic repair in girls by successfully everting the sac into the peritoneal cavity and then using an endoloop [83]. The first successful laparoscopic repair in boys was reported in 1999 by Montupet [84].

In essence, laparoscopic hernia repair in children is an extension of conventional herniotomy involving fundamentally a high ligation of the indirect hernia sac. The reported advantages of the laparoscopic approach include the ease of examining the contralateral internal ring, the avoidance of ‘‘access’’ damage to the vas and vessels during mobilization of the cord, decreased operative time, and an ability to identify unsuspected direct or femoral hernias [85-91]. In a prospective, randomized, single-blind study of 97 patients, the laparoscopic approach was associated with decreased pain, parental perception of faster recovery, and parental perception of better wound cosmesis [89].

Broadly, laparoscopic hernia repairs in children can be classified into two approaches - purely intracorporeal ligation and a laparoscopic-assisted extracorporeal ligation.

Laparoscopic Intracorporeal repair

The first large series of intracorporeal repair was reported by Schier, with primary closure of the peritoneum lateral to the cord with interrupted sutures [85]. This technique was then modified by Schier to use a Z-suture closure rather than interrupted sutures [86]. In girls, in whom injury to the vas deferens and vessels is not an issue, laparoscopic inversion and ligation [83] or excision and closure of the sac can be used [92]. Other modifications include an N-suture instead of a purse-string suture [90] and the ‘‘flip-flap’’ hernioplasty, in which two folds of peritoneum are used to cover the inguinal ring similar to the ‘‘vest over pants’’ repair [94, 95]. This technique theoretically has an advantage of allowing the scrotum to drain through the ‘‘slit’’ that is created, preventing postoperative hydroceles; however, there is only short follow-up, and there are no reports of the incidence of recurrence for this procedure.

Laparoscopic-assisted extracorporeal repair

In laparoscopic-assisted extracorporeal closures, a small stab wound is made over the inguinal ring, and a suture is passed through the abdominal wall behind the peritoneum. It is then directed around the internal ring, avoiding the vas deferens and vessels, and passed out the same stab wound. It is tied extracorporeally under laparoscopic visualization [88, 96-105]. Over the last few years, the technique has evolved from use of two ports to a single port laparoscopic repair with an extracorporeal component. In a two port technique, the variations on the extracorporeal technique have included using an endoneedle [96,100], Reverdin needle [101], using a ‘‘Lapher closure,’’ which consists of a wire on the end of a 19-gauge needle that allows the purse-string suture to be passed [99] and using an Obwegeser maxillary awl to pass the suture [88]. These instruments are introduced percutaneously (in the inguinal region) under laparoscopic guidance and manipulated around the medial or lateral hemi-circumference of the internal ring extraperitoneally, in sequence, to place a purse-string around the internal ring. A grasper, placed through a separate port, is used to manipulate the thread in and out of the hollow of these needles to form a mattress suture. The two ends of the thread then are pulled from the operating port, after which the knot is tied extracorporeally and pushed inside with or without a knot pusher. This technique reduces the need for the second working port and thus only two ports are required- a camera port for visualisation and a working port for guiding the needle.

In a single port extraperitoneal technique, the technique is similar to that described earlier, rendering working ports, endoscopic instruments, and most important, the need for intracorporeal knotting unnecessary. The internal ring is looped under endoscopic control using a 1-0 or 2-0 absorbable suture swaged on a large needle (36–40 mm, curved round body) introduced percutaneously using a strong conventional needle holder [102-105]. The technique has not been standardized yet and there is a high risk of collateral damage and also recurrence if done in inexperienced hands [103,105].

Laparoscopy in incarcerated hernias:

Schier in 2006 reported that creation of pneumoperitoneum itself dilates the ring sufficiently aiding in reduction of the incarcerated contents [106]. In addition, external compression, forbidden in conventional surgery, is found to be safe and useful because the contents can be observed from inside. Even gentle traction with endoscopic instruments is safe under vision and can facilitate reduction of hernia contents immensely. Further viability of the incarcerated intestine can be assessed and if contents prove unviable, as a result of strangulation, they can be excised without adding to the morbidity. In addition, intracorporeal repair is performed in non-edematous tissue at the internal ring [106,107].

Rarer forms of hernia (Direct/ femoral or combinations thereof)

Laparoscopy has a unique advantage of diagnosing rare hernia forms such as direct or femoral hernia forms. Also, combinations of these such as pantaloon hernia and all three hernias (indirect, direct and femoral hernia) have been reported to occur in the same pediatric patient [87, 108,]. With a magnified view from inside, the defect can be clearly visualised and the appropriate repair performed. Repair for a direct or a femoral hernia is different technically from an indirect inguinal hernia [87, 108]. Direct and femoral hernias are discussed in more detail below.

Laparoscopy in recurrent inguinal hernia

For recurrent hernias after previous open herniotomy, re-operation with the open method needs to go through the old operation site which in boys almost always has the vas deferens and testicular vessels embedded in dense fibrous tissue. The operation is always tedious and possesses the danger of damaging these important structures. In such a scenario, the laparoscopic approach allows an approach from the virgin area and helps avoid the previous operation site. So in effect, technically it may as simple as a fresh laparoscopic hernia repair and can be done quite expeditiously.

Also, laparoscopy accurately identifies the nature of the defect in children with recurrent groin hernias, detecting unsuspected contralateral indirect, direct, or femoral hernias in a large number of those undergoing laparoscopy [109-111].

Complications of laparoscopic hernia repair

Personal View

In our experience, children who undergo open herniotomy for a unilateral hernia have a very rapid recovery, are discharged within a few hours and are ambulatory shortly thereafter. Post-operative pain is not much of a concern and acetaminophen is adequate and no antibiotics are required. A minimally invasive unilateral hernia repair by laparoscopic approach seems more invasive in terms of anesthesia and makes a purely extraperitoneal procedure an intraperitoneal one. Laparoscopy does have a definite advantage in selected circumstances such as:

Direct Inguinal hernia

Although congenital direct inguinal hernias are rare in children, they do occur. In two of the largest series of inguinal hernias operated by open technique, the incidence of direct hernia has been less than 1% [52,115]. In the latter series, a third of these had undergone a previous hernia repair on the same side "for presumed indirect hernia". In another series of 1600 inguinal hernia operations, 14 children had direct hernias (0.9%), and half of these were recurrences [116]. Schier also highlighted the similar fact that due to rarity of these hernias, they are often missed and end up having recurrence [108,114].

Intra-corporal view during a laparoscopy may help in a reaching a correct diagnosis and avoid diagnostic pitfalls and subsequent recurrence. Classically an “indirect hernia” defect will be located lateral to the epigastric vessels, “direct hernias” defect opens medially to the epigastric vessels and “femoral hernias” are those which opened medially to the femoral vessels and below the inguinal ligament [87].

The principles of repair and the techniques include closing the defect in an anatomical fashion without prosthetic materials. Pediatric tissues have greater elasticity, and primary repair is usually much more straightforward than in the adult population [17, 108]. Also, laparoscopic repair with strengthening by the median umbilical ligament has been reported to be more successful [108].

Further, sometimes indirect and direct sacs may coexist, the so called hernia-en-pantaloon or pantaloon hernia [52,87,108]. Laparoscopy provides a better elucidation for these rarer hernias and also if the hernia has recurred after a previous open surgery [87].

Femoral Hernia

Femoral hernias in children are rare, difficult to diagnose, and require a different treatment approach than the standard indirect inguinal hernia repair. The incidence is less than 1% of all hernias as reported in various series [87, 117-124]. These hernias are exceedingly rare in infants, usually presenting in older children [117, 123]. They often present as recurrent hernias after inguinal hernia repair, most likely because the surgeon was misled by the findings of a processus vaginalis at the initial surgery and missed the actual hernia defect [87, 117-119].

As discussed previously (vide supra), laparoscopy may help in correct diagnosis in most instances, but a surgeon needs to be aware that these hernias may not be that rare as previously thought and that they may also very rarely exist in combination with other direct or indirect hernias [87].

Femoral hernia can be repaired by open technique such as the classic McVay repair [117-119] or by one of the various laparoscopic techniques recently described. These include laparoscopic mesh plug or patch repair [120,121], use of the umbilical ligament as a plug for laparoscopic repair [122] and laparoscopic assisted inversion of the sac and endoloop closure [124]. Schier recommends a proper dissection of the peritoneum, exposing the underlying defect and anatomy thoroughly and then closing the defect with multiple interrupted sutures to avoid recurrences [87].

HYDROCELE

Hydrocele is a collection of serous fluid in the tunica vaginalis and may extend up into a patent processus vaginalis.

Hydroceles may be classified as:

Symptoms:

Hydroceles are clinically evident anomalies whereby the child is noted to have enlargement of the scrotum. Hydrocele is very common in newborn babies occurring in upto 10% of the male babies.

Examination: Enlargement of the scrotum is observed on inspection and there may be a loss of scrotal rugae with larger hydroceles. Most of the hydroceles are confined to the scrotum but in the inguinoscrotal hydrocele the swelling may be observed going upto the inguinal region. There is no change in size with the straining, crying or coughing, except in a communicating hydrocele.

On palpation, the testis can be felt separately in most of the cases except in a very large, tense hydrocele. In a hydrocele which is limited to the scrotal region the spermatic cord would feel normal at the root of the scrotum while in the inguinoscrotal hydrocele the swelling can be palpated proceeding right into the inguinal canal. The swelling may be felt to be fluctuant, though in a tense hydrocele the fluctuation may be difficult to elicit. Mostly, hydroceles are non-reducible in nature even if there is a patent communication with the peritoneal cavity as the communication is usually small; and works as a ball valve mechanism. Some of the hydroceles may have a fluctuation in size and may be reducible clinically. In these cases the differentiation between a hydrocele and a hernia becomes less important as these are treated the same way as a hernia.

Trans-illumination remains the most important test to diagnose a hydrocele and differentiate it from a hernia. It is a remarkably simple & rapid test and many a mistakes can be avoided by taking two minutes to perform this test in the out-patient department. A small pencil torch with a pointed beam is required for this examination and this should form essential equipment in the office of all physicians dealing with small children. Hydroceles in children are always brilliantly transilluminant while hernias do not allow much light transmission; this difference allows a quick and consistent method to distinguish a hernia from a hydrocele.

Encysted hydrocele of the cord is a special type of hydrocele whereby a localized fluid collection occurs along the spermatic cord anywhere from internal ring to the testicular upper pole. Such encysted hydroceles are often tense swellings and due to their predominance in the inguinal region, they may not be amenable for eliciting transillumination. The key test is to palpate the swelling while keeping the testis in a slight traction. Then the movement of the swelling is assessed with respect to the cord structures. In an encysted hydrocele the movement of the swelling becomes restricted and often it can be felt to slide down with the cord when the cord is pulled caudad.

Investigations: In most cases, a good and thorough clinical examination suffices and no further investigations are required. When in doubt especially, in an encysted hydrocele of cord, an ultrasound examination may be required to rule out other differentials such as inguinal lymph node enlargement. Similarly, if transillumination and physical exam fail to identify the testis, an ultrasound may be considered to rule out the rare case of a reactive hydrocele in response to an instrascrotal process such as inflammation, torsion of the appendix testis and neoplasm.

Management

A newborn or infantile asymptomatic (so-called pure) scrotal hydrocele (no evidence of associated hernia or communication) has a high chance of spontaneous resolution when the patient reaches 1 to 2 years of age [52,125-128]. Thus a watchful expectancy should be offered to such boys with a 3-6 monthly review unless the hydrocele is very large and tense or increases rapidly. On the other hand, a majority of surgeons recommend surgery for a communicating hydrocele, though from 1996 to 2003 the number of surgeons electing to wait for surgery increased [64, 128]. A recent report has challenged this knee jerk operative view by suggesting that even for communicating hydroceles in infancy, spontaneous resolution rate may be more than 60% [129]. Out of 110 infants with a communicating hydrocele at presentation, only 40% required surgery and only 6 progressed to a clinical hernia. On a short term follow-up, in boys in whom a clinical resolution was observed, 2 were found to have a hernia later on in follow-up. No episodes of incarceration were observed, possibly due to small PPV in such cases. A recent study with limited follow-up, it will be important to observe long term assessments to determine if any further hernias develop. If indeed this is a long term resolution, then it deserves to be incorporated into the management protocol and offered to the patients.

Ein in a largest single series of hernias so far suggested that boys with the later onset of a scrotal hydrocele should be considered to have an accompanying hernia and offered surgery upfront [52]. Christensen et al though showed that even in late onset hydrocele, if the clinical history and examination are suggestive of a non-communicating hydrocele, there is still a reasonable (75%) chance of spontaneous resolution. A watchful expectancy of 6-9 months was recommended [130].

There is some debate in the literature about management of encysted hydroceles of the cord.A majority of physicians recommend surgery for a cord hydrocele considering it to be consistent with an indirect inguinal hernia even if the cord hydrocele disappeared before operation [52, 64,128,129]. In our personal experience, cord hydroceles in infants have a high rate of spontaneous resolution though it may not be as high as scrotal hydroceles. If a hernia component is definitively ruled out, waiting until 18 months of age even for encysted hydroceles of the spermatic cord is reasonable.

Surgical Approach to hydroceles

In pediatric hydroceles, in most of the cases, a patent processus vaginalis would be found and would required to be ligated during surgery. So, a standard surgical approach as for hernia is used for hydroceles in children (vide supra).

Upto 10% the processus may found to be obliterated during exploration. In such cases dissection to look for a PPV through an inguinal incision potentially increases the risk of cord injury with a subsequent increased risk of testicular atrophy or reduced fertility [130, 131]. Unfortunately, there are no definite guidelines or means to identify this non-patency pre-operatively.

One aid to identify a PPV during surgery is intraoperative injection of a methylene blue solution into a hydrocele sac. A PPV is identified as a blue line. Anatomy of a PPV was better delineated in encysted hydrocele or a in a recurrent case facilitating dissection and thus minimising the risk of cord damage [130].

Scrotal approach for a non-communicating hydrocele was first reported by Belman [132]. Infants with large abdominoscrotal hydrocele have an obliterated processus and have been seen to do well after a purely scrotal approach. Inguinal incision in such babies is associated with a higher risk of damage to cord structures and a higher incidence of a persistent scrotal component [133,134].

Age may also be considered while deciding for the surgical access. Wilson et al reported that as the age advances the incidence of a patent processus decreases justifying a pure scrotal approach in boys more than 12 years of age [135]. Again in this report and accompanying discussion it was stressed that a good clinical history and examination to confirm a non-communicating hydrocele is a must before proceeding with a scrotal approach. Also, once the hydrocele sac is opened, it may be wise to do a retrograde probing to confirm the absence of PPV.

Conclusion

The pedaitric hernia and hydrocele comprise a spectrum of scrotal disorders that are commonly encountered in routine pediatric practice. A clinical history of the temporal and quantitative nature of the swelling is as important as the findings on physical exam in differentiating a potential surgical case from one that may be observed. A clear understanding of the inguinal anatomy, adequate magnification and experience will ensure success in the repair of these processes.

Legends to Figures:

References

Dr. Arbinder K.Singal

MBBS, M.Ch Ped. Surg.

Pediatric Urologist

MITR Healthcare, Kharghar

MGM Medical College & Hospitals, Navi Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

Aseem R. Shukla, M.D., F.A.A.P.

Director, Pediatric Urology

University of Minnesota Amplatz Children’s Hospital

Associate Professor of Urology

University of Minnesota Department of Urology