Bladder Exstrophy

Blake Palmer, Dominic Frimberger, Bradley Kropp

University of Oklahoma

→ Enlace a la versión en español

→ Enlace a la versión en español

Bladder exstrophy is a rare genitourinary malformation that, when simply defined, refers to the eversion of the bladder to the outside of the body (Figure 1).It is a rare genitourinary malformation for which the management still challenges the field of pediatric urology.

Incidence

The incidence of bladder exstrophy was originally estimated between 1:10,000 and 1:50,000 live births [ ]. However, more recent data from the International Clearinghouse for Birth Defects monitoring system and the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Nationwide Inpatient Sample from the United States estimated the incidence to be 2.15 - 3.3 per 100,000 live births. , There is a male predominance with the male to female ratio has been reported between 2.3-6:1 [ , , ].

Embryology

Mesodermal ingrowth between the ectodermal and endodermal layers of the bilaminar cloacal membrane results in formation of the lower abdominal musculature and pelvic bones. After mesenchymal ingrowth occurs, downward growth of the rectal septum divides the cloaca into a bladder anteriorly and a rectum posteriorly. The genital tubercles migrate medially and fuse in the midline cephalad to the dorsal membrane before it perforates. The cloacal membrane is subject to premature rupture depending on the extent of the infraumbilical defect. The stage of development when the membrane rupture occurs determines whether bladder exstrophy, cloacal exstrophy, or epispadias results [ ].

The most related theory of embryonic development in exstrophy, held by Marshall and Muecke [ ], describes the basic defect as an abnormal lower overdevelopment of the cloacal membrane, which prevents the medial migration of the mesenchymal tissue. Therefore proper development of the abdominal wall does not occur. The timing of the rupture of this cloacal defect determines the severity of the disorder. Central perforations resulting in classic exstrophy have the highest incidence (60%) whereas exstrophy variants account for 30% and cloacal exstrophy 10%.

Other theories are offered concerning the cause of the exstrophy-epispadias complex. Ambrose and O’Brian postulated that an abnormal development of the genital hillocks with fusion in the midline below rather than above the cloacal membrane result in the exstrophy defect [7]. Another hypothesis describes an abnormal caudal insertion of the body stalk with failure of the interposition of the mesenchymal tissue in the midline [ ]. As a consequence of this failure, translocation of the cloaca into the depths of the abdominal cavity does not occur. A cloacal membrane that remains in a superficial infraumbilical position represents an unstable embryonic state with a strong tendency to disintegrate [ ]. No one theory seems to elucidate all aspects of the complex seen clinically and further study is ongoing to fully describe the developmental process that ultimately forms the exstrophy-epispadias complex.

Inheritance

Evidence exists for a genetic predisposition for exstrophy and epispadias. The risk of recurrence of bladder exstrophy in a given family is approximately 1 in 100 [ ], much greater than in the general population. There are many reports of twins with exstrophy. At the same time, however, there are also reports of identical twins with both having exstrophy and another set in which only one was affected. There are numerous cases of nonidentical twins in which only one sibling was affected. These twin sets were found in both male and female pairs [1,4]. Concordance analyses of twins with bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex also suggest a genetic etiology [ ]. A report of 151 families with exstrophy-epispadias complex found 4 multiplex families for a rate of 2.7% [ ]. The likelihood of an exstrophic parent producing a child with exstrophy is about 1:70 live births or 500 times the risk for the general population [4].

Many efforts have been made to understand the possible etiologies of the exstrophy-epispadias complex. The early developmental hormonal milieu associated with in vitro fertilization has been postulated to be involved based on studies that showed a 7.5-fold increase in exstrophy and cloacal exstrophy associated with the use of assisted reproductive technology such as introcystoplasmic sperm injection [ ]. Another epidemiology study showed an increased rate of exstrophy-epispadias complex births to women who underwent in vitro fertilization [ ].

The CASPR3 gene on chromosome 9 has been implicated by Boyadjiev and colleagues to be associated with the exstrophy complex [ ]. Another set of genes on the 9th chromosome has been identified to associate with bladder exstrophy [ , ]. Genetic studies are attempting to determine where and if specific genetic factors can be found that are related to the exstrophy-epispadias complex. Multiple other possible gene loci have been identified but not confirmed [ ].

Prenatal Diagnosis

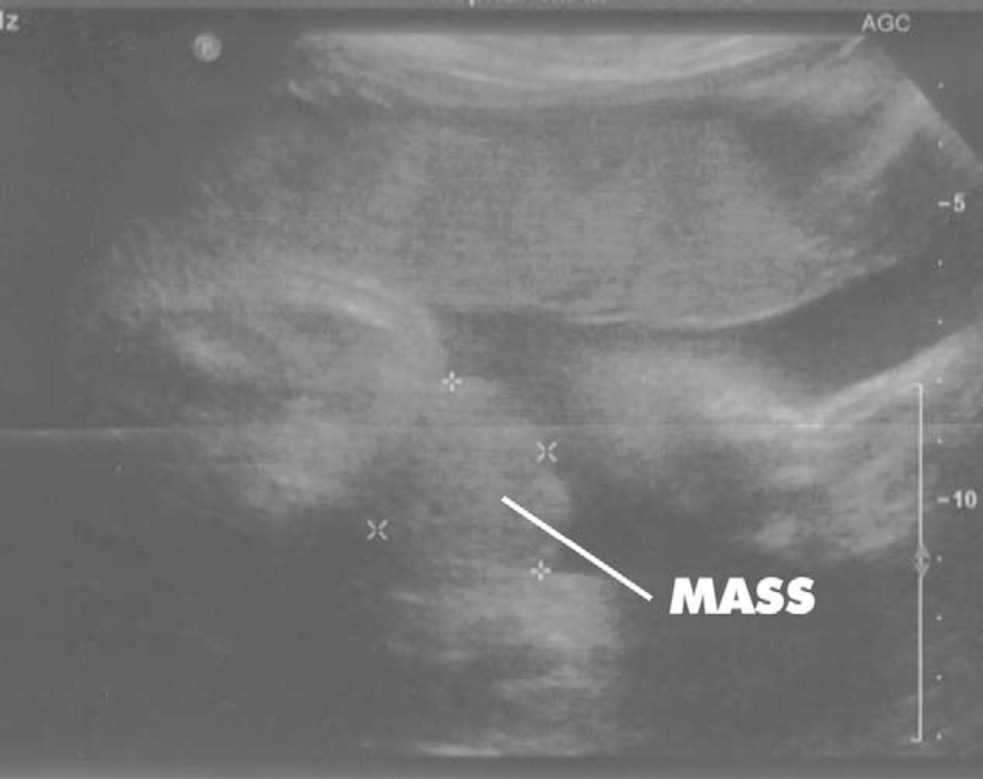

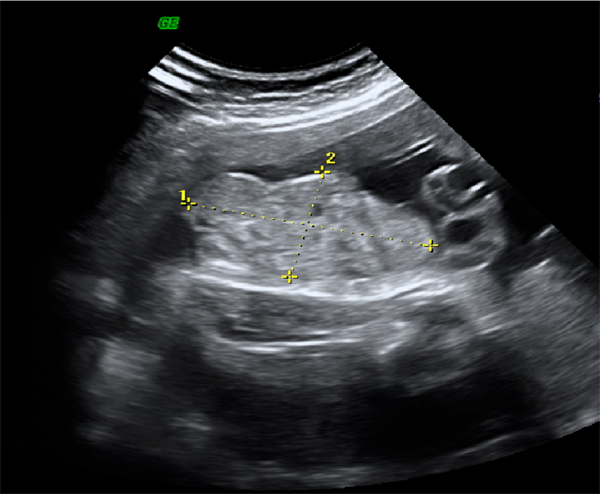

Despite the magnitude of the defect in the lower abdominal wall and pelvic organ development, exstrophy of the bladder is still difficult to diagnose reliably by prenatal ultrasound. This is likely because of its rare incidence and that it is often mistaken for more common diagnoses of omphalocele or gastroschisis. Several groups have illustrated ultrasound findings important in the prenatal diagnosis of exstrophy. In a review of 25 prenatal ultrasounds with subsequent birth of a newborn with classic bladder exstrophy Gearhart et al [ ] described the main criteria for the prenatal diagnosis of exstrophy. This criteria included the (1) absence of bladder filling, (2) lower abdominal mass which becomes more protuberant as the pregnancy proceeds, (3) a low-set umbilicus, (4) separation of the pubic rami, and (5) difficulties determining the sex of the baby. In analyzing this data, bladder exstrophy should always be suspected on the basis of non-visualization of the bladder.

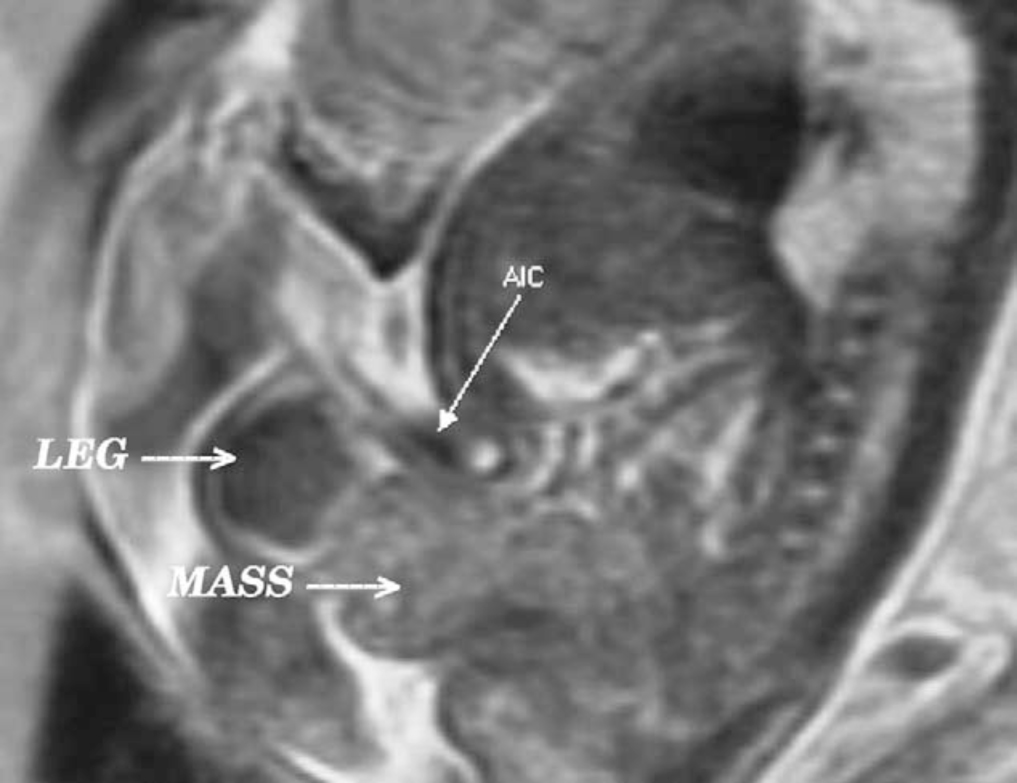

It is felt that 3-D ultrasound and the increasing use of fetal MRI will improve the ability to diagnosis bladder and cloacal exstrophy [ ]. Prenatal diagnosis allows for prenatal counseling and arrangements to be made for delivery at a specialized exstrophy center. This allows for a multidisciplinary approach by teams with experience dealing with the unique nature of the exstrophy-epispadias complex. This includes availability of reconstructive teams in the immediate newborn period and psychosocial support for the parents and families.

The diagnosis of bladder exstrophy is made (or confirmed) at birth with visualization of the bladder plate characteristically protruding beneath the umbilical cord with divergent rectus muscles on either side leading to widely separated pubic bones.

Skeletal Defects

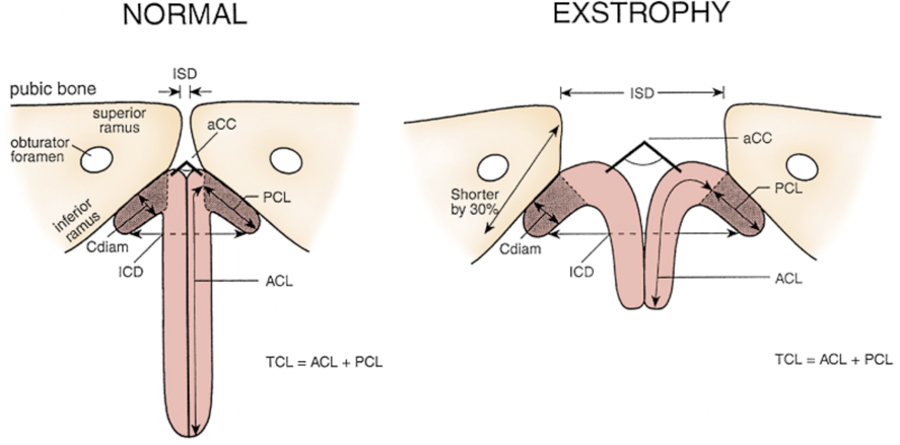

The most obvious skeletal defect is the separation of the pubic bones, which is caused by the outward rotation of the innominate bones, eversion of the pubic rami, and a 30% shortage of bone in the pubic ramus [ ]. The mean external rotation of the posterior aspect of the pelvis was 12-degrees on each side, retroversion of the acetabulum, and a mean 18-degrees of external rotation of the anterior pelvis was determined by 3-D CT reconstructions. Further use of 3-D CT scans showed that the SI joint angle (before closure) was 10-degrees larger in the exstrophy pelvis compared to age-matched controls and 10-degrees more toward the coronal plane than sagittal. The bony pelvis was also 14.7-degrees inferiorly rotated. The sacrum was 42.6% larger by volume measurements and had 23.5% more surface area. These deformities of the pelvic bones contribute to the shortened phallus, waddling gait, and outward rotation of the lower limbs in exstrophy patients. A study of 299 bladder exstrophy children indicated that spinal variations occur without clinical significance: spina bifida occulta, lumbarization or sacralization of vertebrae in 11%, uncomplicated scoliosis in 2.7%, and spinal dysraphism in 4%, including myelomeningocele, lipomeningocele, scimitar sacrum, and hemivertebrae. Only one patient demonstrated evidence of neurologic dysfunction [ ].

Pelvic Floor Defects

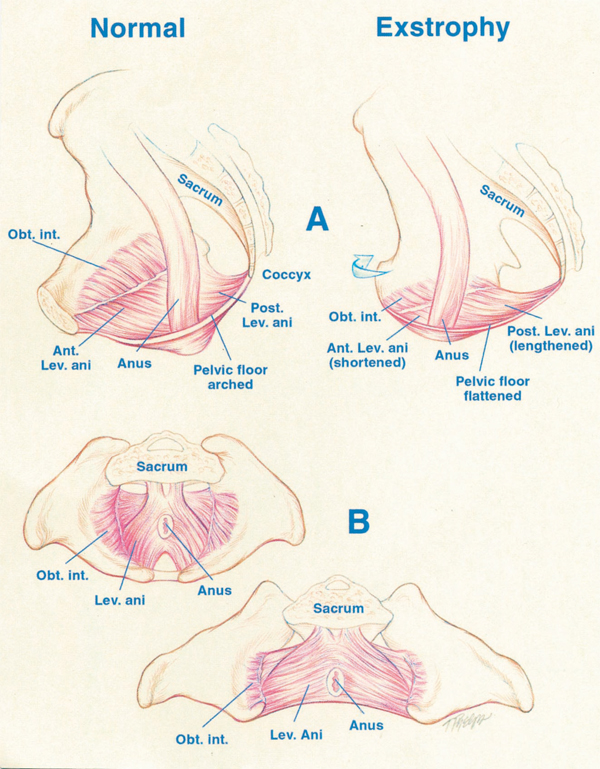

Data by Stec et al. utilizing 3-D CT imaging demonstrated that the puborectal slings in classic bladder exstrophy patients support two times more body cavity than normal age-matched controls [ ]. While the levator muscle group in normal controls is evenly distributed posterior to anterior (52% to 48%) to the rectum, there is an uneven 68% to 32% posterior to anterior distribution in the exstrophy pelvis. There is also a significant flattening of the levators. A 31.7-degree decrease in the steepness is seen between the right and left halves of the levator ani and puborectalis sling. Consequently the anus is anteriorly placed and sometimes patulous as a part of the posterior extent of the myofascial defect. These musculoskeletal malformations explain the increased rate of rectal prolapse, especially in the female exstrophy population.

Further study of the pelvic floor has been done with 3-D MRI and has impacted the understanding of the exstrophy pelvis for reconstruction. Williams et al. demonstrated that the levator ani group was less dome shaped and more irregular in the exstrophy population prior to closure when compared to normal controls. There was also no relationship seen between the degree of pubic diastasis and the extent of disproportionate curvature of the levator ani muscle group. Review of post-closure pelvises by MRI revealed that in those with some degree of continence the intrasymphyseal distance was noted to be the shortest, the angle of the levator ani divergence sharpest, and the bladder neck most deeply positioned in the pelvis [ ]. Gargollo reported on MRI before and after exstrophy closure, noting that the puborectalis angle in those with dry intervals was decreased compared with that prior to closure [ ]. New reports of the use of 3D perineal ultrasound to evaluate the pelvic floor of adult exstrophy females showed that the ultrasound findings correlated well with MRI findings [ ]. These reports reinforce the necessity for aggressive dissection and posterior placement of the posterior urethra and bladder along with good reapproximation of the pubis at the time of closure. Osteotomies and pelvic fixation should be utilized if reconstruction is not done in the immediate newborn period.

Abdominal Wall Defects

There is a triangular defect as a result of the premature rupture of the abnormal cloacal membrane in the abdominal wall, and it is occupied by the exstrophy bladder and posterior urethra. This defect in the fascia is limited inferiorly by the intrasymphyseal band that represents the divergent urogenital diaphragm and connects the bladder neck and posterior urethra to the pubic rami. Wakim and Barbet investigated the relationship of the rectus muscle and fascia to the urogenital diaphragm and found no gross or histologic evidence of the striated sphincter [ ]. They did find evidence of bladder musculature extending laterally to the pubis where it interdigitates with fibers from the rectus fascia to form the fibrous urogenital diaphragm. The importance of radical incision of these fibers lateral to the urethral plate down to the level of the inferior pubic ramus and levator hiatus for the bladder and posterior urethra’s position deep in the pelvis were demonstrated by Gearhart and colleagues, using data from failed exstrophy closures where these fibers were intact at the time of reclosure [ ].

At the cephalad, limit of the triangular fascial defect is the umbilicus. The distance between the umbilicus and anus is foreshortened in bladder exstrophy because the umbilicus is well below the horizontal line of the iliac crest. Although an umbilical hernia is usually present, it is typically insignificant in size and repaired at the time of initial exstrophy closure.

Inguinal hernias are common. They are due to a lack of obliquity of the inguinal canal combined with large internal and external rings and persistence of the processus vaginalis. Connolly and associates reported an 81.8% incidence of inguinal hernia in males and 10.5% in females [ ]. It is recommended to explore the inguinal canals at the time of exstrophy closure and excise the hernia sac with repair of the transversalis fascia and muscular defect to prevent recurrence or a direct hernia.

Anorectal Defects

The exstrophy patient’s perineum is short and broad and the anus directly behind the urogenital diaphragm. It is anteriorly displaced and corresponds to the posterior limit of the triangular fascia defect. The anal sphincter complex is also anteriorly displaced and should be preserved intact. These anatomic factors contribute to varying degrees of anal incontinence and rectal prolapse. Rectal prolapse frequently occurs in untreated exstrophy patients with a widely separated symphysis. Usually this is transient, easily reduced and disappears after bladder closure or cystectomy/urinary diversion. The appearance of prolapse of the rectum is also an indication to proceed with definitive management of the exstrophied bladder. If it occurs at any time after exstrophy closure, posterior urethra/bladder outlet obstruction should be suspected and immediate evaluation of the outlet tract by cystoscopy should be performed [ ].

Male Genital Defects

The male genital defects are severe and challenging at the time of reconstruction. The phallus is short due to 50% deficiency in anterior corporal length [ ] with preservation in posterior length of the corporal body when compared to age-matched controls by MRI. The diameter of the posterior corporal segment was greater than in normal controls. The diastasis of the symphysis pubis increased the intrasymphyseal and intracorporeal distances, but the angle between the corpora cavernosa was unchanged because the corporal bodies were separated in a parallel fashion. This results in a penis that appears short because of the diastasis and the marked congenital deficiency of anterior corporal tissue. Releasing the dorsal chordee, lengthening the urethral groove, and mobilizing the crura in the midline to somewhat lengthen the penis can result in a functional and cosmetically pleasing phallus.

Gearhart and associates used MRI to demonstrate in 13 adult men with bladder exstrophy that the volume, weight, and maximum cross-sectional area of the prostate appeared normal compared with published controls [ ]. However, they found that in none of the patients evaluated did the prostate extend circumferentially around the urethra, and the urethra was anterior to the prostate in all patients. The free and total PSA levels in adult bladder exstrophy men were found to be measureable but below the upper limits of established age-specific references ranges for normal men [ ]. There is a single report of a 56 year-old epispadias patient having prostate cancer with a PSA of 4.2 at the time of biopsy [ ].

The vas deferens and ejaculatory ducts are normal in the exstrophy patient as long as they are not injured iatrogenically during closure or reconstruction. The mean seminal vesicle length was found to be normal.

The autonomic nerves that innervate the corpus cavernosum (cavernous nerves) are displaced laterally in exstrophy patients [ ] and these nerves are preserved in almost all exstrophy patients as potency is preserved after surgery. Retrograde ejaculation is found to occur after bladder closure and bladder neck reconstruction.

Testes frequently appear to be retractile but have adequate length in the spermatic cord to reach the flat, wide scrotum without need for orchiopexy. The testes have not been studied in a large group of postpubertal exstrophy patients but are generally believed to be not impaired. D’Hauwers et al. reported the use of percutaneous sperm aspiration and intracytoplasmic sperm injection, and state in 3 exstrophy patients they had good success with sperm harvesting [ ].

Female Genital Defects

In girls, the mons, clitoris, and labia are separated and the vaginal orifice is displaced anteriorly and stenotic. The clitoris is bifid and the vagina is shorter than normal controls but of normal caliber. The cervix is found on the anterior vaginal wall because the uterus enters the vagina superiorly. The fallopian tubes and ovaries are usually normal. The bifid clitoris should be reapproximated with the two ends of the labia minora to form a fourchette at the time of primary closure. Commonly, vaginal dilation or an episotomy may be required to allow satisfactory intercourse in the mature female. A study of 56 adult women found that 10 developed uterine prolapse at a mean age of 16 years. Six of whom had previously had reconstruction that included a posterior iliac osteotomy at a mean age of 2.1 years [ ].

Urinary Defects

The exposed bladder mucosa is susceptible to cystic or metaplastic changes and, therefore, must be irrigated frequently with saline and protected from surface trauma and exposure by a protective membrane until surgical bladder closure can be preformed. Commonly plastic wrap (i.e., Saran Wrap) is sufficient. The mucosa at birth can have a segment of ectopic bowel mucosa, an isolated bowel loop, or most commonly hamartomatous polyps.

Shapiro and colleagues characterized the neuromuscular function of the bladder. They showed that muscarinic cholinergic receptor density and binding affinity were similar in exstrophy and control subjects [ ]. Bladder biopsies from 12 newborns with bladder exstrophy, compared to age-matched controls, found an increase in the ratio of collagen to smooth muscle in the exstrophy bladders[ ]. The type of collagens were analyzed and a normal distribution of type I collagen was present, but a threefold increase in type III collagen was found. It was later seen that those patients who demonstrated bladder growth by measuring capacity after successful closure, who were free of infection had a markedly decreased ratio of collagen to smooth muscle [ , ]. Primary cultures of exstrophy bladder smooth muscle cells were shown to have growth characteristics similar to those previously reported in non-exstrophy cells, showing that they likely retain their potential for growth and function [ ]. Mathews and associates found that the average number of myelinated small nerve fibers per field was significantly reduced in the exstrophy bladders compared with controls [ ]. Preservation of larger nerve fibers was seen, which led the study to hypothesize that bladder exstrophy in a newborn represented an earlier stage of bladder development. Multiple immunocytochemical and histochemical markers, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), neuropeptide Y (NPY), substance P (SP), calcitonin gene-related product (CGRP), protein gene product (PGP) 9.5, and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate diaphorase (NADPHd) have been studied, and there was no evidence of bladder muscle dysinnervation morphologically in any cases of bladder exstrophy [ ]. However, cases of bladder exstrophy after failed reconstruction did have muscle innervation deficiencies that increased subepithelial and intraepithelial innervations. Microarray analysis of exstrophic bladder smooth muscle compared to ‘healthy’ controls showed what appears to be a developmentally immature finding in the exstrophy bladder smooth muscle [ ]. Therefore, it is felt that although the bladder in an exstrophy patient may be immature it has the potential for normal development after a successful initial closure.

Bladder plate polyps were found to be two types with overlapping findings: fibrotic and edematous. Both were associated with overlying squamous metaplasia in 50% of cases. Varying degrees of von Brunn’s nests, cystitis cystica and cystitis glandularis were noted. Cystitis glandularis was noted in a higher percentage of secondary closures. Future surveillance of those cystisis glandularis patients is recommended given their potential risk for adenocarcinoma. This can be done with urine cytology and cystoscopy as they enter adulthood [ ].

The bladder plate may invaginate or bulge through a small fascial defect at birth but the true estimate of the bladder plate cannot be evaluated completely until the newborn is under anesthesia and fully relaxed. A small, fibrosed, inelastic bladder and/or one that is covered with polyps may make a functional repair challenging and potentially impossible.

Normal cystometrograms were obtained in 70-90% of those assessed in a group of continent exstrophy patients with normal reflexive bladders [ ]. An evaluation of 30 exstrophy patients at various phases of modern staged repair prior to bladder neck reconstruction found 80% to have compliant and stable bladders after bladder neck reconstruction. Approximately half maintained normal bladder compliance and fewer maintained normal stability. It was felt by the authors of that study that 25% of exstrophy patients might maintain normal detrusor function after reconstruction [ ]. The microstructure of the bladder of exstrophy patients at various points in modern staged repair was found to have different caveoli (important intracellular structures for cell-cell signaling). These caveoli were felt to be normal in those with a successful closure and improving bladder capacity but lacking in those who required an augmentation cystoplasty. They noted that the ultrastructure of cells also was abnormal in the group that failed initial closure [ ].

The remainder of the urinary tract is usually normal but anomalies do occur. Horseshoe kidney, pelvic kidney, hypoplastic kidney, solitary kidney, and dysplasia with megaureters can all be encountered. The course of the ureter is abnormal in terms of termination. Because the peritoneal pouch of Douglas, between the bladder and the rectum, is enlarged and unusually deep, the ureter is forced down laterally in its course across the true pelvis. The distal segment approaches the bladder inferiorly and laterally to the orifice. This results in vesicoureteral reflux in 100% of exstrophy cases. Ureteral reimplantations are done at the time of bladder neck repair but sometimes are needed sooner. If there are problems with infections and excessive outlet resistance, ureteral reimplantation may be needed prior to bladder neck reconstruction or at any point if severe reflux and upper tract issues develop.

Evaluation and Management at Birth

In the delivery room the umbilical cord should be tied with 2-0 silk close to the abdominal wall so the umbilical clamp does not irritate or traumatize the exposed bladder mucosa. The bladder mucosa should be frequently irrigated with warm saline and always covered with a protective clear plastic wrap until the time of closure. The bladder should be irrigated and plastic wrap changed at each diaper change.

A multidisciplinary approach is important. The team should include, but not be limited to, a pediatric urologist, pediatric orthopedic surgeon, pediatric anesthesiologist, neonatologist, pediatric psychiatrist (with expertise and experience in genital anomalies) and social workers. Studies have proven that the parents of exstrophy patients experience a significant amount of stress. The parents stress should not be overlooked during the initial and long-term care of the patient [ ]. The parents should be reassured that children with classic bladder exstrophy are generally healthy, robust infants with the prospect of leading a very normal life. Effective reconstruction to allow urinary storage, drainage, and control can be expected with acceptable cosmetic appearance. The support of psychologists, nurses, and parents of other children with exstrophy is invaluable and available at an Association of Bladder Exstrophy Children (ABC) certified center. The ABC website (www.bladderexstrophy.com) also offers further information for parents and families.

A neonatologist should evaluate the patient from a general pediatric and cardiopulmonary standpoint with the likelihood of major surgery in the first 48 hours of life. A cardiac echo is commonly done to rule out significant cardiopulmonary anomalies that would preclude early reconstruction. A renal ultrasound should be obtained to evaluate the upper urinary tracts. A KUB is done to evaluate the pelvis bony anatomy and a spinal ultrasound to rule out an associated spinal dysraphism.

It is essential that a pediatric genitourinary surgeon with experience and interest in the exstrophy-epispadias complex evaluate the newborn exstrophy patient, as the impact of a major birth defect is significantly worse by inappropriate initial management [ , , ].

In those patients with ambiguous genitalia in addition to bladder exstrophy the parents should be educated and counseled by a multidisciplinary disorders of sexual differentiation team but should understand that the need to change the gender rearing in classic bladder exstrophy is almost nonexistent in the male infant with current reconstructive outcomes.

As many of these cases still go undetected until the time of delivery, most will require transport to an exstrophy center soon after birth. During travel, the bladder should be protected by a clear plastic membrane and kept moist to protect the delicate bladder mucosa.

Surgical Reconstruction

The goals of surgical reconstruction in the exstrophy patient are to correct the urogenital defects providing a reservoir that is adequate for urinary storage at low pressures with the ability to empty completely without compromising renal function, to create functional and cosmetically acceptable external genitalia, and to maximizing patient quality of life.

Early attempts at bladder exstrophy were unsuccessful and patients had short life expectancies. Therefore, for many years the management for exstrophy consisted of removal of the exstrophic bladder and urinary diversion commonly by ureterosigmoidostomy. Various staged repairs began to show early success in the 1950s [ ]. In the 1970s, the preliminary constructs of staged repair that are utilized today were initiated [ , , ]. This developed into the modern staged repair of exstrophy [ ] that is commonly used today. In the late 1980s an anatomical approach to exstrophy repair began and has been modified into what is now referred to as the complete primary repair of exstrophy or Mitchell technique [ ]. Currently, most patients are managed either with a complete primary repair of exstrophy (CPRE [65]) or modern staged reconstruction of exstrophy (MSRE) [ ]. A great deal of discussion continues regarding the optimal treatment of exstrophy in the newborn period. With that in mind, ureterosigmoidostomy remains a popular and preferred reconstruction in many parts of the world because it reliably achieves urinary continence and is relatively safe for those without access to dependable health care facilities or a specialized exstrophy centers [ ].

Complete Primary Repair of Exstrophy

The CPRE is the most recent development in surgical management of exstrophy patients pioneered by Dr. Mitchell [63]. This approach has been adopted and reproduced by multiple centers of excellence for exstrophy management. In the CPRE, an anatomic approach to reconstruction includes bladder closure with bladder neck remodeling and a disassembly technique for epispadias repair with or without osteotomies in one setting [ ]. It is felt this allows for bladder cycling and more ‘normal’ growth and development because the bladder experiences an outlet resistance. The disassembly technique for epispadias repair also allows for division of the intersymphyseal ligaments and appropriate anatomic placement of the bladder neck and posterior urethra deep into the pelvis in its orthotopic position [ ]. When done within the first 72 hours of life, the pelvis is malleable enough to close without osteotomies. The patients still necessitate Bryant’s traction for approximately 1 week and then lower extremitiy casting for 3 weeks to prevent tension on the pelvis closure. The incidence of dehiscence and bladder prolapse is rare in the modern day [ ].

The CPRE is advocated as an approach to allow for maximal development of the bladder and define those patients whose bladders will grow and develop earlier than those managed in a staged manner. Normalizing the anatomy at the initial closure just after birth may have other benefits such as minimizing the family’s psychosocial trauma. Patients whose bladder does develop will likely undergo fewer procedures than in a staged fashion.

Continence has been reported after CPRE to be 76%, defined as dry intervals longer than 2 hours and spontaneous voiding without catheterizations [ ]. However, a significant percentage of patients will likely still require a formal bladder neck procedure to achieve continence [ ]. In another series, 75% of patients after CPRE were continent with intervals of 4 hours and dry at night with 31.3% requiring CIC [ ].

Concerns with the CPRE are related to potential for renal deterioration related to a high pressure lower urinary system, risk of penile injury or loss with disassembly at such a young age, and requirement for multiple procedures despite the name ‘complete repair.’ Close follow-up of the upper tracts is important in exstrophy regardless of repair. Hydronephrosis, pyelonephritis and renal scarring are seen after CPRE and should be managed aggressively with prophylactic antibiotics since vesicoureteral reflux is expected post operatively. Long-term follow-up in the Seattle series shows that mild (45%), moderate (17.8%), and severe (7.1%) hydronephrosis is seen after CPRE. But half of those with hydronephrosis, and in all with severe hydronephrosis, it was transient [ ]. Borer and associates reported an incidence of pyelonephritis of 28% and DMSA renal scaring of 19% after CPRE [70]. The need for bilateral ureteral reimplantation after CPRE exclusive of those done at the time of bladder neck repair are seen to be 25-34% [70,71,72].

Approximately 36-68% of patients will be left with a hypospadias after CPRE that will require further penile surgery [63,69,70,71,72, ]. Glans necrosis, penile skin loss and/or penile tissue loss has been reported after CPRE but is quite rare when performed at an exstrophy centers of excellence [ , ].

Comparing the number of procedures that a patient may be expected to undergo is a controversial topic when comparing the CPRE and MSRE. Reports vary widely about the number and types of procedures and the reports are fraught with potentials for bias making it difficult to draw true conclusions on this subject [75]. However, it is accepted that patients managed in a CPRE and MSRE approach will likely require multiple procedures and the outcomes are better if managed at a center of excellence for exstrophy.

Modern Staged Reconstruction of Exstrophy

The MSRE as now practiced has evolved from the original work by Cendron [59] and Jeffs. [60] The Hopkins group, led by Dr. Gearhart, currently has the largest exstrophy population and writes the majority of the literature regarding the MSRE [ ]. In the MSRE, the goal at initial reconstruction is to convert the exstrophic bladder to a complete epispadias. Pelvic osteotomies are performed in conjunction with bladder closure when indicated. It is felt that this will allow for protection from renal dysfunction because the patient is still incontinent but can also stimulate bladder growth since there is now some bladder outlet resistance. The epispadias repair is performed between 6-12 months of age and testosterone stimulation is provided preoperatively. The bladder neck repairs for continence is performed between 4-5 years of age if they have an adequate bladder capacity and are determined to be ready to participate in a postoperative voiding program [76]. If these criteria are not met, the patient is left incontinent until the bladder grows and maturity improves or they are diverted with an augmentation with a catheterizable channel and bladder neck closure when necessary.

Continence rates are reported by Gearhart in males to be 70% and females to be 74% with dry periods greater than 3 hours with spontaneous voiding and dry at night without CIC [76, ]. They have concluded that a bladder capacity of 100 ml predicts success at the time of bladder neck reconstruction utilizing the modified Young-Dees-Leadbetter repair. This increased the chance of continence and time to achieve continence in their reviews [76,77]. If this 100 ml capacity is not achieved it is felt they should undergo an augmentation at the time of reconstruction for continence. They also found that females were more likely to achieve continence and at a shorter duration after bladder neck reconstruction [77]. Their reports also show similarly low complication rates. In males after closure, epispadias, and bladder neck reconstruction the total complication rate was 41.7% with one incidence of primary closure failure [76]. In females after bladder closure and bladder neck reconstruction the total complication rate was 19.5% [77]. In their modern series if successful bladder growth occurs 19.4% of males and 17% of females failed bladder neck reconstruction and have undergone or will require an augmentation with a catheterizable stoma and bladder neck closure as indicated [76,77].

In the MSRE, if a patient’s bladder capacity does not develop to the level that predicts success with bladder neck reconstruction, the patient is moved directly to an augmentation for continence. This is reasonable but clouds comparisons between MSRE and CPRE. The MSRE reports those that complete the series. Because the CPRE performs a continence procedure at the initial closure, they are including those patients whose bladders may not have developed and never been a candidate for a bladder neck reconstruction had they been managed by MSRE. Also, it is difficult to determine how many, if any, of those bladders that did not develop to 100 ml capacity by continence age would have grown had they had a CPRE at initial closure with increased outlet resistance available to promote development. There also may be a certain subset of exstrophy bladders that are ‘bad’ and will not grow regardless of closure technique but are unable to be identified at birth. These factors make it difficult to define success and failure when comparing techniques. Further long term prospective analysis needs to continue in an unbiased and open minded fashion to promote the interchange of ideas that can hopefully lead to the next breakthroughs in management of exstrophy that will continue to improve the quality of life of these patients.

Summary of Agreed Upon Surgical Reconstruction Tenants

Sexual Function in the Exstrophy patient

There are reports of adult male exstrophy patients fathering or initiating a pregnancy that show that fertility is possible in these patients although it may not be commonplace. Shapiro’s large series of 2500 patients only documented 38 males who had fathered children [4]. Semen analyses studies comparing men who underwent primary repair to ureterosigmoidostomy diversion found a normal sperm count in only one of eight in the closure group and in four of eight in the diverted group [ ]. These differences were attributed to retrograde ejaculation and iatrogenic injury during functional closure of the bladder. Another study found that none of their reconstructed patients could ejaculate normally nor had they fathered children. Five patients who had not undergone reconstruction had normal ejaculation and two had fathered children [ ]. This leads to the conclusion that the male patient is a high risk of infertility after reconstruction. The use of assisted reproduction in any fashion has been shown by Bastuba and coworkers to be successful in 13 males with exstrophy that led to successful pregnancy with no incidence of exstrophy in the offspring [ ].

Woodhouse reported that the sexual function and libido of the exstrophy patient is normal [ ]. Multiple reports show that erectile function is maintained in a vast majority after urethral and phallic reconstruction, and that ejaculation is often not normal but is usually present. Most reported satisfactory orgasms, and described intimate relationships as serious and long-term [79, ].

The female external genitalia are now routinely fully reconstructed at the time of exstrophy closure. Previously this reconstruction consisted of a cosmetic reapproximation of the bifid clitoris and anterior labia to make a fourchette but did not address the inherent anatomic abnormality of the vaginas location and angle relative to the abdomen and perineum in exstrophy females [ ]. Further reconstruction during adolescent years, prior to initiation of sexual activity or use of tampons in some female exstrophy patients was not uncommon [ ]. An application of the total urogenital complex mobilization was applied and resulted in successful correction of the location and angle of the vagina in female exstrophy patients [81]. Successful intercourse has been reported in all patients in one study and dyspareunia was reported in a minority [82]. A large series also reported that female exstrophy patients greater than 18 years of age had normal sexual desires and many were sexually active with normal orgasms [ ]. Some patients were self-conscious of and limited their sexual activity because of the cosmetic appearance of their external genitalia. A monsplasty is an important part of reconstruction in females and use of hair bearing skin and fat to cover the midline defect is routine. A later repair with the use of rhomboid flaps was reported with good success [ ].

Obstetric and Gynecologic Implications

Many women with bladder exstrophy have successfully delivered normal offspring (45 women with 49 children in one report) [ ]. Another study showed 40 women, ages 19 to 36 that were treated for bladder exstrophy as infants, and out of those 40 women 14 pregnancies were reported in 11 women. Out of those 14 pregnancies were 9 normal deliveries, 3 spontaneous abortions, and 2 elective abortions. Uterine prolapse occurred in 7 of the 11 patients during pregnancy [ ]. It is seen to be very common for these women to have cervical and uterine prolapse after pregnancy and delivery [85]. In these early reports, all women apparently had undergone prior permanent urinary diversions but recent reports show that successful pregnancies have been reported in women who have undergone continent urinary diversions [ ]. Cesarean sections were preformed in women with functional bladder closures to eliminate stress on the pelvic floor and to avoid traumatic injury to the urinary sphincter mechanism [85].

Pelvic organ prolapse appears to be a significant problem in female exstrophy patients. It is commonly seen during and after pregnancy or delivery, possibly in up to half of patients [82]. It can occur at young ages and without prior sexual activity or pregnancy [82,83]. The anterior displacement of the vaginal os and marked posterior displacement of the dorsorectalis sling and its deficient anterior compartment were theorized as reasons for significant findings of prolapse [64]. It is felt that more modern reconstruction of the pelvic floor and anatomical replacement of the bladder into the pelvis and use of osteotomies may improve this troubling problem. Previous reports showed that uterine suspension was only modestly successful in prevention of recurrent prolapse [64]. However, Stein reported that uterine fixation by sacrocolpopexy corrected prolapse in 13 females with greater than 25 years of follow-up [ ].

Cloacal Exstrophy

Cloacal exstrophy is the most severe defect that can occur in the formation of the ventral abdominal wall and represents the most severe anomaly of the exstrophy spectrum that is compatible with viability. This entity is extremely rare, occurring in 1 in 200,000-400,000 live births [ ]. The male to female ratio has most recently been reported in a large contemporary study to be equal between the sexes, 1:1 [14]. Most cases are sporadic. However, isolated incidences of unbalanced translocations have been reported to be potentially causative by Thauvin-Robinet et al [ ]. Although it is likely multifactorial, genetic studies continue to help determine potential etiologies.

In the past, children with cloacal exstrophy did not survive past the newborn period. In 1960, Rickham reported the first patient with cloacal exstrophy to survive surgical reconstruction [ ]. The omphalocele was repaired, the intestinal strip was separated from the hemibladders, and the blind-ending colon was pulled through to the perineum. The hemibladders were then reapproximated. An ileal conduit was constructed at the age of 18 months and a cystectomy was performed later. After early reconstruction, the patient was left with two stomas. With advances in critical care and current anatomic repairs, most patients now can live well into adulthood. The focus of care and research is now on improving the quality of life of these patients [ ].

Anatomic Anomalies

Cloacal exstrophy includes findings of exstrophy of the hindgut/bladder complex, complete phallic separation, wide pubic diastasis, prolapsing terminal ileum, imperforate anus, and an omphalocele. Cloacal exstrophy is considered part of the OEIS complex when seen coexisting with omphalocele, imperforate anus, and spinal defects [ ].

The lower urinary tract is typically composed of two exstrophied hemibladders adjacent to the midline exstrophied intestinal segment. Each bladder is drained by its ipsilateral ureter and is in close approximation to the hemiphallus on the ipsilateral side. Variations, however, are frequent.

Neurospinal Anomalies

Neurospinal abnormalities have been noted in 85-100% of patients with cloacal exstrophy [ , ] with a distribution of lumbar (80%), thoracic (10%) and sacral defects (10%). A single center review of 34 patients found 17 lipomeningoceles, 8 myelomeningoceles, 7 with spina bifida, and 2 with isolated cord tethering [92]. It is also reported that only 1 in 5 children with spinal dysraphism by ultrasound has a defect appreciated on physical exam [ ]. Since there is an almost ubiquitous neurospinal defect it is recommended that all cloacal exstrophy patients have a spinal evaluation by ultrasound or MRI. It is reported that spinal ultrasound findings are comparable to MRI for the diagnosis of spinal anomalies in newborns with cloacal exstrophy. Ultrasound is quicker, easier, and less expensive to perform and does not require sedation [ ]. Therefore, all children with cloacal exstrophy should have a spinal ultrasound.

The functional deficits in the cloacal exstrophy patient can vary widely from almost normal sensation of the pelvis and lower extremity to severe impairments rendering the patient wheelchair bound. The presence of a significant neurologic deficit is associated negatively with the ability to develop continence [ ].

Schlegel and Gearhart first described the neuroanatomy of the pelvis in the child born with cloacal exstrophy [ ]. The autonomic innervation to the bladder halves and corporal bodies arises from a pelvic plexus on the anterior surface of the sacrum. The phallus is usually separated into a right and left half with adjacent scrotum or labia. Occasionally, the penis is together in the midline, but the structure is diminutive and the corporal bodies are small.

The nerves to the hemibladders travel along the midline on the posteroinferior surface of the pelvis and extend laterally to the hemibladders. The autonomic innervation of the phallic halves arises from the sacral pelvic plexus, travels in the midline, perforates the inferior portion of the pelvis floor, and courses medially to the hemibladder. This more medial location of the autonomic bladder innervation makes it easy to injure at the time of initial bladder dissection and reconstruction, which creates a neuropathic bladder [98].

McLaughlin and associates postulated that the embryologic basis for the neurospinal defects in cloacal exstrophy were secondary to problems with the disruption of the tissue of the dorsal mesenchyme, not the failure of neural tube closure [95] It has also been suggested that the defects associated with the formation of cloacal exstrophy could pull apart the developing spinal cord and vertebrae [ ].

Skeletal Anomalies

The pelvic defects in cloacal exstrophy are similar in nature but more severe than that in bladder exstrophy. Sponseller and associates described the pelvic anatomy using CT scans in the cloacal exstrophy population [ ]. The interpubic diastasis was found to have a mean of 0.5 cm in controls and 8 cm in cloacal exstrophy patients, which is almost twice that of bladder exstrophy patients. The anterior segment length (distance from the triradiate cartilage to the pubis) was 37% shorter in cloacal exstrophy patients. Also, the angle of iliac wing was markedly increased at 45-degrees, showing the extreme amount of external rotation. Likewise, the ischiopubic angle was clearly increased in the cloacal exstrophy children. Overall, patients with cloacal exstrophy have extreme abnormalities of the pelvis: asymmetry between the sides, sacroiliac joint malformations, and occasional hip malformations. The long bone lengths are relatively similar to those with bladder exstrophy. Microscopically, the bones in children with cloacal exstrophy were similar to those in normal controls and were seen to develop at a similar rate.

Skeletal and limb anomalies were reported in 12-65% of cases of cloacal exstrophy [ ]. Most were clubfoot deformities, but absence of feet, severe tibial or fibular deformities, and congenital hip dislocations were also commonly seen in this group of patients. This was confirmed by Greene’s report of a high incidence of foot abnormalities and abduction of the hip [ ].

Gastrointestinal Anomalies

Omphaloceles are reported in more than 88-100% of cloacal exstrophy [92,103]. The omphaloceles can vary widely in size and usually contain small bowel contents, liver, or both. Immediate closure of the omphalocele defect is recommended to prevent subsequent rupture and evisceration.

Other significant gastrointestinal anomalies were reported in 46% of cloacal exstrophy patients [ ]. Such anomalies included malrotation, bowel duplication, duodenal atresia, duodenal web, and Meckel’s diverticulum. Ultimately, short gut syndrome is reported in 25% of cloacal exstrophy patients [103]. Short gut syndrome can also be encountered in the presence of normal small bowel length suggesting an absorptive dysfunction. The importance of preserving as much bowel as possible and utilizing the hindgut remnant in bowel reconstruction and not using it for later urogenital reconstruction as has been performed in the past.

Upper Urinary Tract Anomalies

Several series have demonstrated the common occurrence of upper tract anomalies (41-60%). The most common anomalies encountered were pelvic kidneys and renal agenesis, hydronephrosis and hydroureter, which occurred in up to one third of patients [103]. Multicystic dysplastic kidneys and fusion anomalies were reported. Ectopic ureters were seen to be able to drain into the vas in the male and into the uterus, vagina, or fallopian tubes in the female. Ureteral duplication, congenital stricture, and megaureters were also seen.

Mullerian and Testicular Anomalies

The most common mullerian anomaly reported was uterine duplication (95%) [103] with most having partial duplication, predominately a bicornate uterus. Duplication of the vagina (65%) [ ] and vaginal agenesis (25-50%) have also been reported. Gearhart and Jeffs recommended preserving all mullerian duplication anomalies for possible utilization in reconstruction of the lower urinary tract [ ].

In two series of reviews by Hurwitz and et al [105] as well as Ricketts and colleagues [ ], the testes were undescended and found in the groin or abdomen and commonly associated with inguinal hernias.

Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Anomalies

Life-threatening anomalies of the cardiovascular and pulmonary systems are rare. However, there are case reports of patients with cyanotic heart disease, aortic duplication, vena caval duplication, bilobed lung and an atretic upper lobe bronchus.

Prenatal Diagnosis

Austin and colleagues [ ] established major and minor criteria for the prenatal diagnosis of cloacal exstrophy based on the incidence of prenatal ultrasonography findings in 20 patients. Major criteria were found in >50% of cases and included nonvisualization of the bladder (91%), a large midline infraumbilical anterior wall defect or a cystic anterior wall structure (82%), an omphalocele (77%), and a myelomeningocele (68%). The minor criteria included lower extremity anomalies (23%), renal anomalies (23%), ascites (41%), widened pubic arches (18%), narrow thorax in (9%), hydrocephalus (9%), and a single umbilical artery (9%). It has also been suggested to add the characteristic elephant trunk appearance that the prolapsing terminal ileum can produce [ ]. Regardless of the criteria, the entity is very rare and still difficult to diagnosis prenatally. When a prenatal diagnosis is made, the parents should be counseled by an experienced exstrophy genitourinary surgeon and referred to an exstrophy center of excellence for delivery whenever possible.

Neonatal Assessment

The care of these complex patients should occur in an exstrophy center of excellence where there is experience with these patients’ special issues and resources are available. The bowel/bladder plates should be kept moist and protected with warm saline and a clear plastic wrap, as with bladder exstrophy. The infant’s condition at birth may be critical and attempts to reconstruct and repair may be futile or morally and/or ethically unwise. Often the severity of cloacal exstrophy is enhanced by the nature and severity of the associated anomalies. Immediate management is intended to medically stabilize the newborn. Evaluation should involve a multidisciplinary team, as previously discussed, for bladder exstrophy. A thorough discussion and assessment of all the anomalies is important for short and long term reconstructive planning. This should include a discussion regarding gender assignment and should include a disorders of sex differentiation (DSD) team. Ideally, this team would include a pediatric urologist, pediatric surgeon, neonatologist, pediatric endocrinologist, and a child psychologist/psychiatrist. Decisions should only be made after appropriate parental counseling and education. This often will require a chromosomal analysis.

Gender Assignment

The need for gender reassignment is only an issue in those 46XY male cloacal exstrophy patients with inadequate phallic structures for reconstruction. As surgical techniques for phallic reconstruction have evolved, a functional and cosmetically acceptable phallus can now almost always be constructed [ ]. This is true even if only unilateral or partial phallic structures are present. This is obviously a complex procedure that should be managed at a specialized center for best outcomes, surgically and psychosocially.

In the past male to female gender reassignment for male cloacal exstrophy patients was commonplace. Presently, it is the general consensus among experts that it is important to assign gender that is consistent with karyotype in this population if at all possible. This is supported by work from Mathews and associates showing that the histology of testis removed at the time of gender reassignment were normal [ ].

Long-term evaluation of those patients whom were gender reassigned at birth has been studied by Reiner and showed that psychosexual evaluation indicated that all of these patients had a marked shift in psychosexual development despite having no pubertal hormonal surges [ ]. An earlier, smaller evaluation showed that although these patients had masculine childhood behavior, they had a feminine gender identity in their report [ ]. Another study, which compared cloacal exstrophy to other cloacal anomaly patients, showed no difference in social or behavioral competence or psychological problems [ ].

Immediate Surgical Reconstruction

Cloacal exstrophy patient’s reconstructive procedures should be carefully planned and individualized. Among the important decisions to make during the initial operative planning is whether to perform a one- or two-stage closure. A one-stage is preferred if possible to minimize the number of neonatal procedures necessary. This will also allow the bladder to be protected and internalized, thereby reducing the risk of external trauma, polyp formation and potentially improving its chances at normal development. During either a one- or two-stage procedure, the omphalocele is excised, and the bowel is separated from the hemibladders. Care must be taken when the bowel is separated from the bladder halves to avoid damage to the blood supply of the bowel mesentery and the autonomic vesical innervation, which becomes exposed at the medial aspect of the hemibladder. The lateral vesicointestinal fissure is closed in continuity, and a short colostomy is created from the end of the distal colon segment. The hemibladders are then re-approximated in the midline to create a single exstrophic bladder. If a one-stage is selected, the entire bladder is closed completely as in a classic bladder exstrophy patient. Bilateral osteotomies are performed if done after the first 72 hours of life. With a large omphalocele defect, bladder closure and osteotomy may be delayed until respiratory and gastrointestinal stability are achieved [92].

In patients with spinal dysraphism and myelocystocele, a neurosurgical evaluation should be completed and closure undertaken as soon as the infant is medically stable. Long-term follow-up is important since up to 33% of children can have symptomatic spinal cord tethering [95].

Management of the Bowel

Formerly, patients died from fluid and electrolyte loss with a short bowel and terminal ileostomy. It is now accepted that the best and first priority when managing the hindgut segment is careful preservation and incorporation into the gastrointestinal tract to optimize bowel length. It can be used initially as a fecal colostomy, and it may help absorption and prevent fluid loss [ ] Also as the hindgut enlarges, if used for a fecal colostomy, it later could be used as a bladder augmentation or vaginal replacement if nutritional status and prognosis allow [92, ]. Regardless, the primary emphasis should be on salvaging as much bowel as possible.

Placement of the colostomy or ileostomy at a favorable location is important. It should be where it can easily be managed with an appliance. If it is determined as the child ages and grows that an adequate hindgut exists and there are no neurologic deficits then a pull through procedure could be preformed via the posterior sagittal approach [ ]. It is also emphasized that to maximize quality of life in these patients an aggressive bowel management program should be adopted. Most of these patients can be good candidates for a pull-through procedure [ ]. Effort should also be made to maintain any appendiceal structures for later continent stoma construction if necessary.

Management of the Phallus and Vagina

In males with cloacal exstrophy, the penis is usually represented by two widely separated small phallic structures. Because these structures are rudimentary and wide apart, reconstruction is challenging. However, when adequate corporal tissue is present, epispadias repair can be performed at the same time of initial closure, or later, depending on the situation.

If insufficient phallic tissue is present and female sex rearing is chosen, the medial aspects of the bifid phallus are denuded of mucosa and brought together in the midline. This is usually done at the time of bladder closure and osteotomy. If there is a single phallic structure in the midline (20% of patients) the urethral plate is dissected and the corporal bodies dropped between them to the perineum for a urethral opening. The corpora and glands are then recessed for more appropriate female appearance and the labial folds are created from the scrotum by a posterior Y-V plasty. It should be reemphasized that if at all possible these patients should be maintained and reared according to their genetic sex.

Correction of genital anomalies in girls is usually done at the time of bladder closure and osteotomy. The medial aspect of the hemiclitoris is denuded of mucosa and the halves are brought together. Commonly, duplicate vaginas are far apart and on opposite sides of the pelvis. In the unusual case of the vaginas being close together, they should be joined in the midline and used for later reconstruction. The ostia of the vaginas may be difficult to find at the time of the initial closure, and the surgeon should be aware that they could enter the posterior walls of the bladder. It is acceptable to leave the vaginas in situ but further surgery will be need to bring one of these to the perineum.

In the genotypic male patient raised as a female, the vagina usually created at the time of puberty. In the past, vaginas have been created by anatomic “scraps” such as portion of the duplicated bowel, unneeded dilated ureters, or a few centimeters of the distal colonic segment. Therefore, it is debated to wait until puberty and whether or not to construct a vagina from intestine or from a free full-thickness skin graft. There is little data of the neovagina in the cloacal exstrophy patient, but as more of these patients reach puberty, experience with this entity will increase, and long-term information will be available.

Lower Urinary Tract Reconstruction

In the one-stage complete primary repair of exstrophy that is applied to cloacal exstrophy, the hindgut is excised and incorporated into the colostomy as previously described. The two hemibladders are re-approximated in the midline and the omphalocele is repaired and closed giving the appearance of a classic bladder exstrophy patient. The complete primary repair may be attempted in cases where the patient is hemodynamically stable, the omphalocele is small, the pubic diastasis is not wide, and pulmonary function is adequate to tolerate an increased intra-abdominal pressure. If these criteria are not met, the patient’s bladder plate should again be covered and maintained with a plastic wrap with frequent irrigation with saline until the time of definitive management [ ].

If the patient is deemed an adequate candidate the next steps in the complete primary repair can be initiated. Complete penile disassembly and division of the intersymphyseal band are crucial steps to allow for posterior positioning of the bladder and urethra. Then reconstruction of the bladder, penis, abdomen, and pelvis approximates the normal anatomy. Osteotomies are almost always necessary to assist in closure and posterior placement of the lower urinary tract [120]. Postoperative drainage and immobilization are important via ureteral stents, a suprapubic tube and possibly a urethral catheter along with traction and casting similar to that in classic bladder exstrophy.

Osteotomies can be performed with this procedure in cloacal exstrophy patients, as can be done with classic bladder exstrophy closures. If performing a one-stage closure, the pubic bones and pelvis can be re-approximated in the same fashion as in the complete primary repair of classic bladder exstrophy. Regardless, the goal is to achieve tension-free approximation of the widely separated pubic bones and of the anterior abdominal wall. Anterior osteotomy also provides large cancellous surfaces with good healing potential. Furthermore, in cases of extreme pubic diastasis, combined anterior innominate and posterior osteotomy may be done within the periosteum through the same skin incision for better correction. The importance of osteotomy at the time of cloacal exstrophy closure has been demonstrated by Ben-Chaim and colleagues, who showed that 9 of 22 patients were closed without osteotomies and 89% of them had significant complications (dehiscence, vesicocutaneous fistula, prolapse) while there were complications in only 2 of 12 who had an osteotomy at the time of initial cloacal exstrophy closure [ ]. Silver and associates have applied a novel approach to osteotomy in cloacal exstrophy patients with failed prior closures or extreme diastasis [ ]. In this approach, osteotomy is performed along with external fixator placement followed by soft tissue and pelvic ring closure two to three weeks later after the pelvis has been gradually reduced by fixator approximation.

Management of Urinary Incontinence

Incontinence of urine is managed by diapering only during the early years. Intermittent catheterization is likely to be needed for emptying after any procedure to enhance outlet resistance. This may be due in part to spinal defects, which can cause a neurologic deficit in bladder function, or to a small bladder capacity, which may require augmentation. In both instances, bladder detrussor activity usually is impaired. In cases closed with complete primary repair, a bladder septum may play a role in poor bladder function and is hypothesized to be related to residual hindgut remnants that are incorporated in the closure and an alternate procedure may be required to separate this septum when it is identified [120]. The role of bladder outlet repair in cloacal exstrophy is minimal. Husmann and associates clearly showed a very marked difference in continence results between cloacal exstrophy and classic bladder exstrophy [97]. This is likely due in large part to co-existing neurologic abnormalities. Surgery to produce a continent reservoir should be delayed until the child is old enough to participate in self-care. The choice between a catheterizable urethra or an abdominal stoma depends on the adequacy of the urethra and bladder outlet, the intellect and dexterity of the child, and the child’s orthopedic status as regards to the spine, hip joints, braces and ambulation.

Occasionally, hindgut is available for bladder enhancement, but ileum has traditionally been used. In an effort to avoid further loss of absorptive surface by preserving both hindgut and ileum, Adams and colleagues have used stomach for a gastrocystoplasty with good success although long-term cancer concerns exist [ ]. Regardless of which bowel segment is chosen, bladder augmentation should be delayed until bowel function is mature and nutrition and acidosis are no longer a problem.

Some patients with a minimal neurological lesion have a functioning bladder and can void through a reconstructed bladder outlet. Innovative methods may be needed, however, to construct a continent outlet in patients without substantial native urethral tissues. These techniques include use of vagina to form a urethra, with reimplantation of the vagina into the bladder for continence, or an ileal nipple, as described by Hendren [ ]. Urinary continence is possible in most children but usually will require a bladder augmentation and intermittent catheterization in some form [64].

Long-Term Psychological and Psychosexual Issues

With improved survival and reconstructive surgery, long-term adjustment issues have become paramount. Reiner has reported on six children who had undergone gender reassignment, all with developmental difficulties [ ]. None had undergone replacement with exogenous female hormones and most expressed typical male behavior. Two had spontaneous gender assignment and assigned themselves back to the male sex. All had extensive family counseling at birth as well as continued counseling through childhood for the parents and children. In contrast, Shober reported 46 XY cloacal exstrophy patients whom all had feminine typical core gender identity on long-term follow-up [ ]. The patients will have to be followed into adult life for appropriate decision-making and information to be obtained. Also, in the same study, regardless of karyotype, the quality of life of those patients raised female sex was good. All disliked their colostomy and the need to catheterize but the quality of life was rated high.

Summary

The management of cloacal exstrophy has improved to provide more quality of life for these children. Complete reconstruction in the newborn period seems to be the best approach if the infant’s condition allows. Neurological and gastrointestinal management takes precedence over urological and genital repair and the hindgut should be primarily incorporated to maximize bowel length and function. Improvements in neurological evaluation have served to reduce life-threatening complications and the progression of neurological deficits. Urinary incontinence is now possible in most children but requires further reconstruction. Current surgical reconstructive techniques have advanced enough that many more XY patients can be reconstructed and reared male, which appears to be the optimal choice; however, further long-term evaluations are needed to assess their satisfaction. Advances in tissue engineering and stem cell research will likely allow congruent rearing of all male patients with cloacal exstrophy. Further long-term research is mandatory to continue progress in the treatment of these interesting children at specialized centers with experience managing these complex issues with a multidisciplinary team approach.

Palmer et al figure legends

Figure 1. Newborn with classic bladder exstrophy.

Figure 2: 30 weeks’ gestation ultrasound demonstrating nonvisualization of the bladder and a lower abdominal mass.

Figure 3: Sagittal view of bladder exstrophy (mass) below abdominal insertion of the umbilical cord (AIC) on T2 prenatal MRI.

Figure 4: A, displacement of levator (Lev.) ani to more posterior (Post.) position in patient with exstrophy, that is 68% posterior to anus versus normal controls. Also note shortened anterior (Ant.) segment of levator ani in exstrophy 32% anterior to anus versus 48% in controls. Obt. int., obturator internus. B, greater outward rotation of 15.1 degrees of obturator internus in exstrophy group versus controls. Also note that area encompassed by puborectalis is 2-fold that of controls and more flattened.

Figure 5: Penile and pelvic measurements in normal men and patients with exstrophy. ZSD, intersymphyseal distance. UCC, corpora cavernosa subtended angle. Cdiam, corpus cavernosum diameter. PCL, posterior corporeal length. ZCD, intercorporeal dlstance. ACL, anterior corporeal length. EL,total corporeal length

Figure 6: Newborn with classic bladder exstrophy. Note multiple polyps on bladder plate.

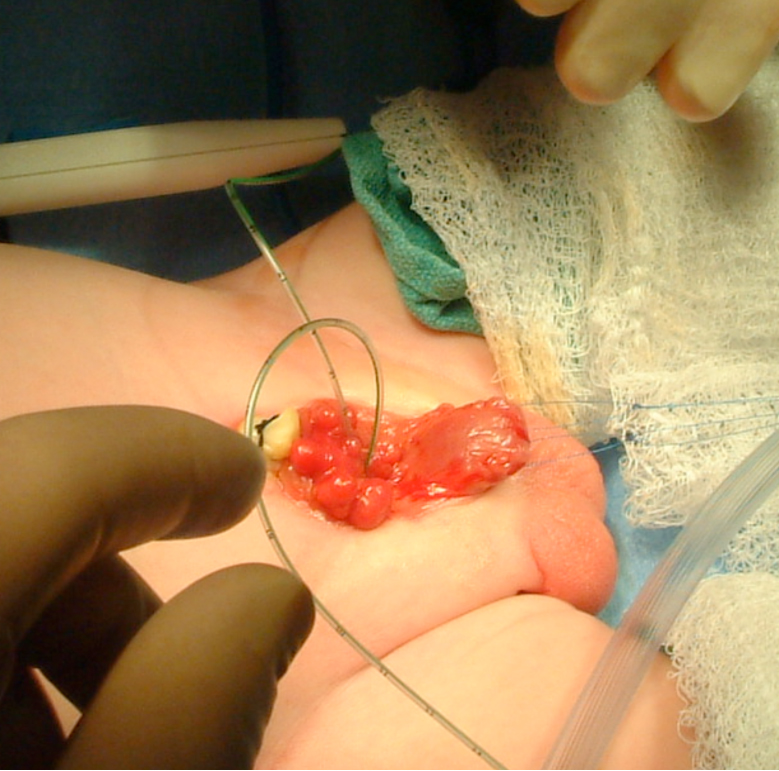

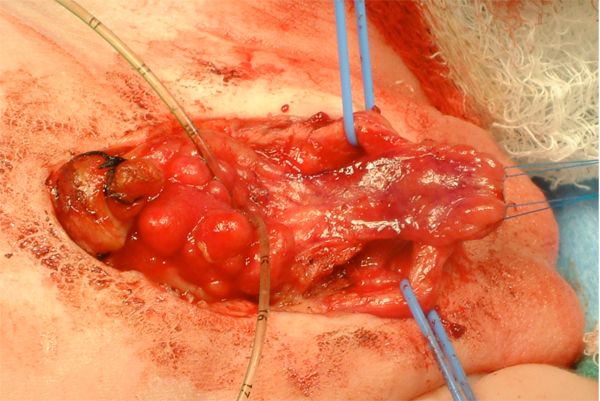

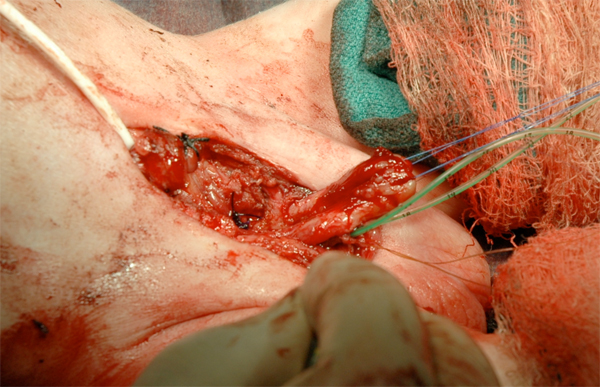

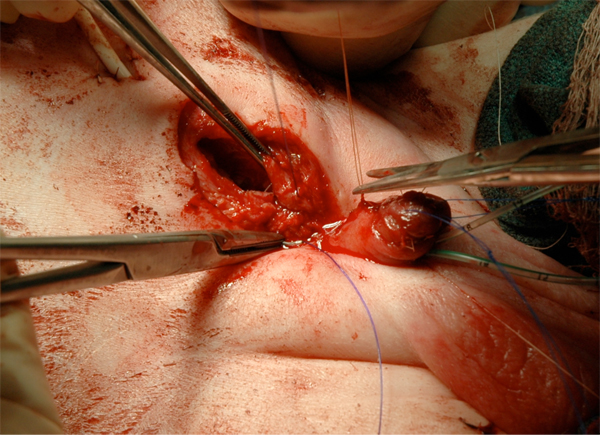

Figure 7: Intubation of bilateral ureteral orifices in preparation for dissection.

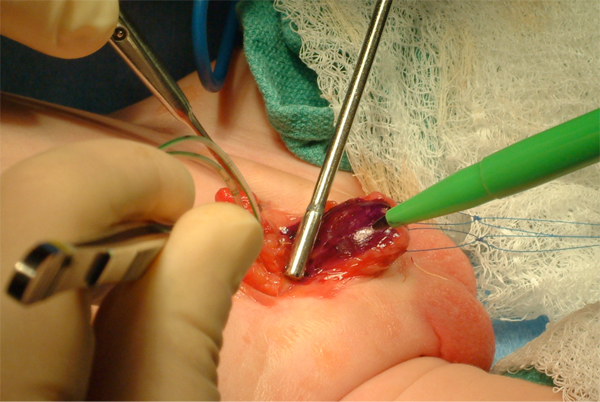

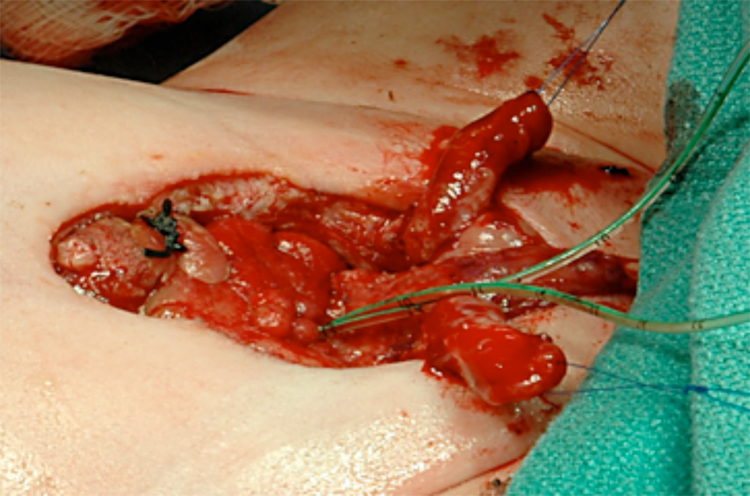

Figure 8: Marking of urethral plate. Notice two traction sutures on each hemiglans.

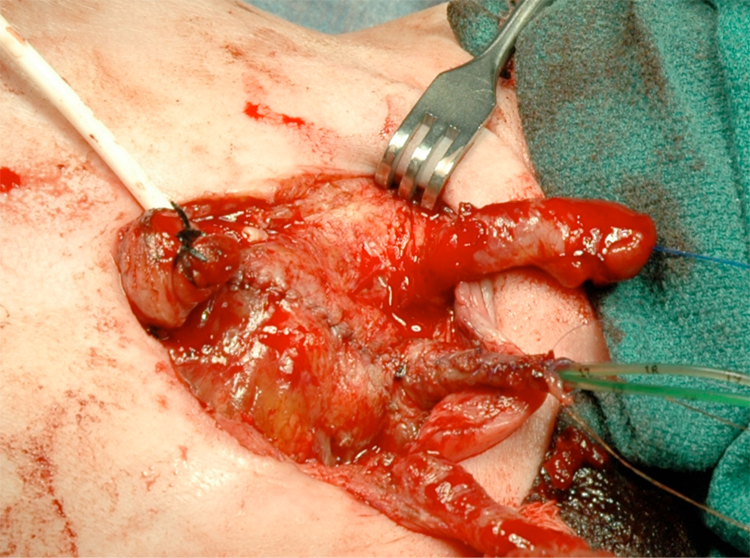

Figure 9: Aggressive bladder mobilization, including the umbilicus.

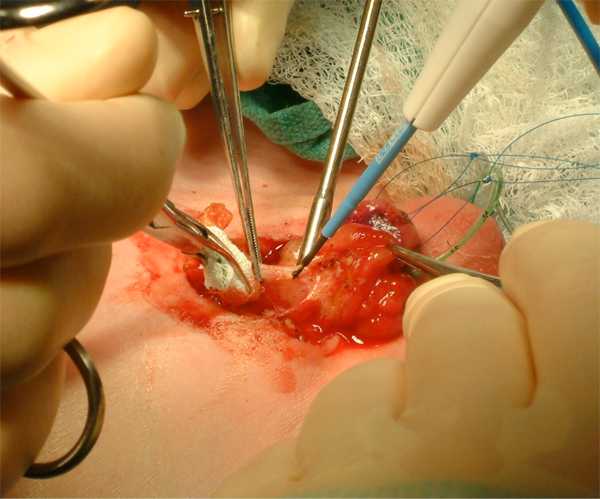

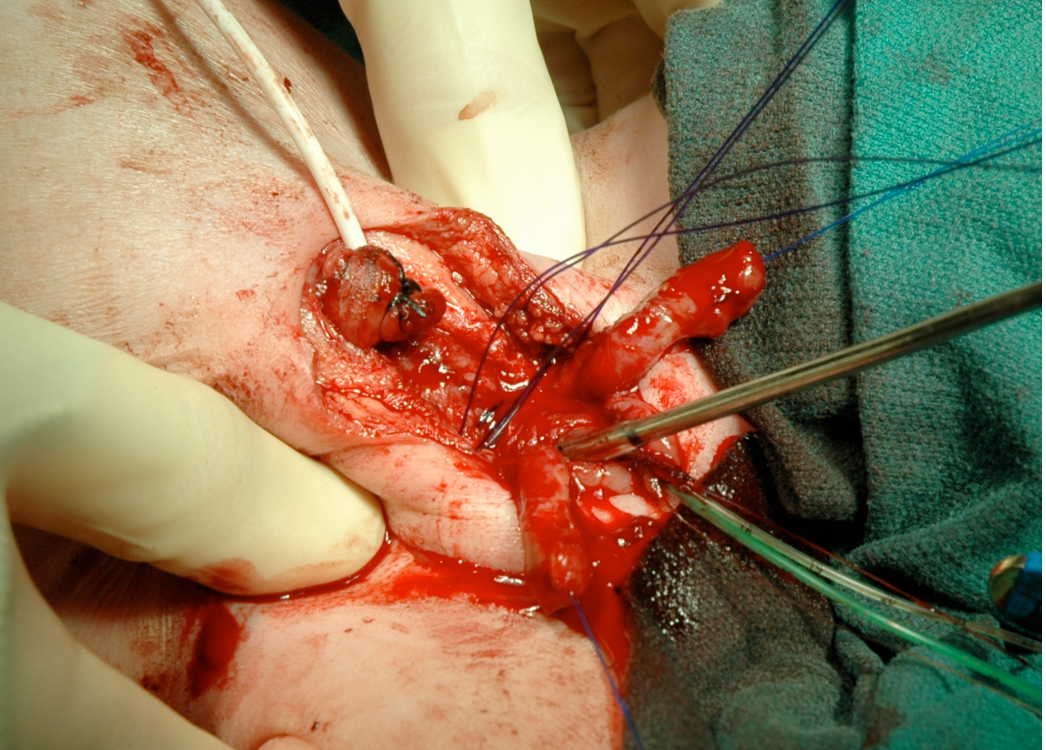

Figure 10: Identification of bilateral corporal bodies after degloving of phallus.

Figure 11: After separation of the corporal bodies and mobilization of the urethral plate.

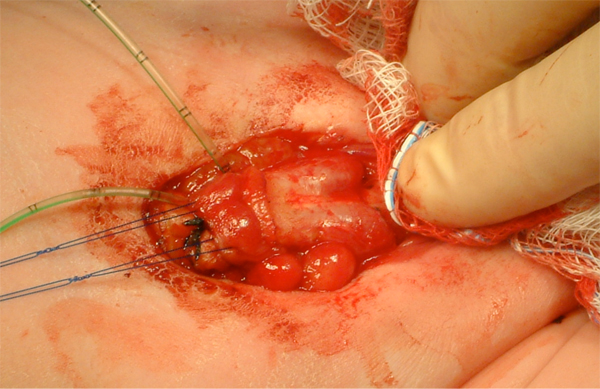

Figure 12: After complete separation of the corporal bodies and glans.

Figure 13: Placement of suprapubic tube prior to bladder closure. This will exit the abdomen at the umbilicus.

Figure 14: Bladder and urethra closed in 2 layers as a single unit. Note bilateral ureteral catheters exiting via the urethral meatus.

Figure 15: Internal rotation of the pelvis to reapproximate the pubis when reconstructed in the first 72 hours of life can be accomplished.

Figure 16: Phallus reconstruction.

Figure 17: Fascial closure.

Figure 18: Abdominal wall closure.

Figure 19: Modified Bryant’s traction.

Figure 20: Postoperative.

Figure 21: Newborn with cloacal exstrophy.

Figure 22: Prenatal ultrasound of female with cloacal exstrophy. Note complex anterior abdominal wall mass inferior to the umbilical cord insertion. No bladder is visualized.

i Hsieh K, O’Loughlin MT, Ferrer FA. Bladder Exstrophy and Pheontypic Gender Determination on Fetal Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Urology 2005; 65:998-999.

ii Hsieh K, O’Loughlin MT, Ferrer FA. Bladder Exstrophy and Pheontypic Gender Determination on Fetal Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Urology 2005; 65:998-999.

iii Stec AA, Pannu HK, Tadros YE, et al: Pelvic floor evaluation in classic bladder exstrophy using 3-dimensional computerized tomography-Initial insights. J Urol 2001;166:1444.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 21

Figure 22

Hsieh K, O’Loughlin MT, Ferrer FA. Bladder Exstrophy and Pheontypic Gender Determination on Fetal Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Urology 2005; 65:998-999.

. Ben-Chaim J, Sponseller PD, Jeffs RD, et al. Application of osteotomy in cloacal exstrophy patients. J Urol 1995;154:865.

. Silver RI, Sponseller PD, Gearhart JP. Staged closure of the pelvis in cloacal exstrophy: first description of a new approach. J Urol 1999;161:263.

. Tank ES, Lindenaur SM: Principles of management of exstrophy of the cloaca. Am J Surg 1970;119:95.

. Gearhart JP, Jeffs RD:. Techniques to create urinary continence in cloacal exstrophy patients. J Urol 1991;146:616.

. Ricketts R, Woodard JR, Zwiren GT, et al. Modern treatment of cloacal exstrophy. J Pediatr Surg 1991;26:444.

. Austin P, Holmsy YL, Gearhart JP, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of cloacal exstrophy. J Urol 1998;160:1179.

. Hamada H, Pakano K, Shinah H, et al. New ultrasonographic criterion for the prenatal diagnosis of cloacal exstrophy: elephant trunk-like image. J Urol 1999;162:2123.

. Husmann DA, McLorie GA, Churchill BM. Phallic reconstruction in cloacal exstrophy. J Urol 1989;142:563.

. Mathews RI, Perlman E, Gearhart JP: Gonadal morphology in cloacal exstrophy: implications in gender assignment. BJU Int 1999;83:484.

. Reiner WG. Psychosexual development in genetic males assigned female: the cloacal exstrophy experience. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am 2004;13:657.

. Schober JM, Carmichael PA, Hines M, Ransley PG. The ultimate challenge of cloacal exstrophy. J Urol 2002;167:300.

. Baker Towell DM, Towell AD. A preliminary investigation into quality of life, psychological distress and social competence in children with cloacal exstrophy. J Urol 2003;169:1850.

. Taghizadeh A, Qteishat A, Cuckow PM. Restoring hindgut continuity in cloacal exstrophy: A valuable method of optimizing bowel length. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2009;19:141.

. Husmann DA, McLorie GA, Churchill BM: Closure of the exstrophic bladder: an evaluation of the factors leading to its success and its importance on urinary continence. J Urol 1989;142:522.

. Hurwitz RS, Manzoni GA, Ransley PG, et al. Cloacal exstrophy: a report of 34 cases. J Urol 1987;138:1060.

. Thauvin-Robinet C, Faivre L, Cusin V, et al. Cloacal exstrophy in an infant with 9q34.1-qter deletion resulting from a de novo unbalanced translocation between chromosome 9q and Yq. Am J Med Genet A 2004;126:303.

. Mathews R, Jeffs RD, Reiner WG, et al. Cloacal exstrophy-improving the quality of life: The Johns Hopkins experience. J Urol 1998;160:2452.

. Keppler-Noreiul KM. OEIS complex (omphalocele-exstrophy-imperforate anus-spinal defects): a review of 14 cases. Am J Med Genet 2001;99:271.

. Appignani BA, Jaramillo D, Barnes PD, et al. Dysraphic myelodysplasias associated with urogenital and anorectal anomalies: prevalence and types seen with MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1994;163:1199.

. McLaughlin KT, Rink RC, Kalsbeck GE, et al. Cloacal exstrophy: the neurological implications. J Urol 1995;154:782.

. Karrer FM, Flannery AM, Nelson MDJ, et al. Anorectal malformations: evaluation of associated spinal dysraphic syndromes. J Pediatr Surg 1988;23:45.

. Dick EA, de Bruyn R, Patel K, et al. Spinal ultrasound in cloacal exstrophy. Clin Radiol 2001;56:289.

. Husmann DA, Vandersteen VR, McLorie GA, et al. Urinary continence after staged bladder reconstruction in cloacal exstrophy: the affect of co-existing neurological abnormalities on urinary continence. J Urol 1999;161;1598.

. Schlegel PN, Gearhart JP. Neuroanatomy of the pelvis in an infant with cloacal exstrophy: a detailed microdissection with histology. J Urol 1989;141:583.

. Cohen AR. The mermaid malformation: cloacal exstrophy and occult spinal dysraphism. Neurosurgery 1991;28:834.

. Sponseller PD, Bisson LJ, Gearhart JP, et al. The anatomy of the pelvis in the exstrophy complex. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995;77:177.

. Stec AA, Wakim A, Barbet P, et al. Fetal bony pelvis in the bladder exstrophy complex: Normal potential for growth? Urology 2003;62:337.

. Baird AD, Nelson CP, Gearhart JP. Modern staged repair of bladder exstrophy: a contemporary series. J Pediatr Urol 2007;3:311.

. Purves JT, Baird AD, Gearhart JP. The modern staged repair of bladder exstrophy in the female: a contemporary series. J Pediatr Urol 2008;4:150.

. Hanna MK, Williams DI. Genital function in males with vesical exstrophy and epispadias. BJU Int 1969;44:1972.

. Bastuba MD, Alper MM, Oats RD. Fertility and the use of assisted reproductive techniques in the adult male exstrophy patient. Fertil Steril 1993;60:733.

. Woodhouse CR. Sexual function in boys with exstrophy, myelomeningocele, and micropenis. Urology 1998;52:3.

. Ben-Chaim J, Jeffs RD, Reiner WG, et al. The outcome of patients with classic bladder exstrophy in adult life. J Urol 1996;155:1251.

. Kropp BP, Cheng EY. Total urogenital complex mobilization in female patients with exstrophy. J Urol 2000;164:1035.

. Mathews RI, Gan, M, Gearhart JP. Urogynaecologic and obstetric issues in women with the exstrophy-epispadias complex. BJU Int 2003;91:845.

. Kramer SA, Jackson IT. Bilateral rhomboid flaps for reconstruction of the external genitalia in epispadias-exstrophy. Plast Reconstr Surg 1986;77:621.

. Krisiloff M, Puchner PJ, Tretter W, et al. Pregnancy in women with bladder exstrophy. J Urol 1978;119:478.

. Burbage KA, Hensle TW, Chambers WJ, et al: Pregnancy and sexual function in bladder exstrophy. Urology 1986;28:12.

. Meldrum KK, Mathews RI, Nelson CP, et al. Subspecialty training and surgical outcomes in children with failed bladder exstrophy closure. J Pediatr Urol 2005;1:95.

. Nelson CP, North AC, Ward MK, et al. Economic impact of failed or delayed primary repair of bladder exstrophy: differences in cost of hospitalization. J Urol 2008;179:680.

. Nelson CP, Dunn RL, Wei JT, et al. Surgical repair of bladder exstrophy in the modern era: contemporary practice patterns and the role of hospital case volume. J Urol 2005;174:1099.

. Sweetser TH, Chisolm TC, Thompson WH. Exstrophy of the urinary bladder: discussion of anatomic principles applicable to repair with a preliminary report of a case. Minn Med 1952;35:654.

. Jeffs RD, Charrios R, Mnay M, et al. Primary closure of the exstrophied bladder. In Scott R (ed): Current Controversies in Urologic Management. Philadelphia:WB Saunders, 1972; 235.

. Gearhart JP, Jeffs RD. State of the art reconstructive surgery for bladder exstrophy at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. Am J Dis Child 1989;143:1475.

. Chan DY, Jeffs RD, Gearhart JP. Determinants of continence in the bladder exstrophy population: predictors of success? Urology 2001;57:774.

. Stein R, Fisch M, Black P. Strategies for reconstruction after unsuccessful or unsatisfactory primary treatment of patients with bladder exstrophy and incontinent epispadias. J Urol 1999;161:1934.

. Grady RW, Mitchell ME. Surgical techniques for one-stage reconstruction of the exstrophy-epispadias complex. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Partin AW, Peters CA (eds). Campbell-Walsh Urology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007, p. 3497.

. Husmann DA. Surgery Insight: advantages and pitfalls of surgical techniques for the correction of bladder exstrophy. Nat Clin Prac Urol 2006:3:95.

. Kibur Y, Roth CC, Frimberger D, et al. Our initial experience with the technique of complete primary repair for bladder exstrophy. J Pediatr Urol 2009;5:186.

. Gargollo PC, Borer JG, Diamond DA, et al. Prospective followup in patients after complete primary repair of bladder exstrophy. J Urol 2008;180:1665.

. Kibur Y, Roth CC, Frimberger D, et al. Our initial experience with the technique of complete primary repair for bladder exstrophy. J Pediatr Urol 2009;5:186.

. Shnorhavorian M, Grady RW, Anderson A, et al. Long-term followup of complete primary repair of exstrophy: The Seattle Experience. J Urol 2008;180:1615.

. Hafez AT and El-Sherbiny MT. Complete repair of bladder exstrophy: management of resultant hypospadias. J Urol 2005;173:958-961.

. Shapiro E, Jeffs RD, Gearhart JP, et al. Muscarinic cholinergic receptors in bladder exstrophy: Insights into surgical management. J Urol 1985;134:309.

. Lee BR, Perlman EJ, Partin AW, et al. Evaluation of smooth muscle and collagen subtypes in normal newborns and those with bladder exstrophy. J Urol 1996;156:203.

. Peppas DS, Blanche-Tijien M, Perlman E, et al: A quantitative histology of the bladder in various stages of reconstruction utilizing color morphometry. In Gearhart JP, Mathews RI (eds): Exstrophy-Epispadias Complex: Research Concepts and Clinical Applications. New York, Plenum, 1999:41.

. Lais A, Paolocci N, Ferro N, et al. Morphometric analysis of smooth muscle in the exstrophy-epispadias complex. J Urol 1996;156:819.

. Orsola A, Estrada CR, Nguyen HT, et al. Growth and stretch response of human exstrophy bladder smooth muscle cells: molecular evidence of normal intrinsic function. BJU Int 2005;95:144.

. Mathews RI, Wills M, Perlman E, et al. Neural innervation of the newborn exstrophy bladder: An immunohistological study. J Urol 1999;162:506.

. Rosch W, Christl A, Strauss B, et al. Comparison of preoperative innervation pattern and post reconstructive urodynamics in the exstrophy-epispadias complex. Urol Int 1997;59:6.

. Hipp J, Andersson KE, Kwon TG, et al. Micoarray analysis of exstrophic human bladder smooth muscle. BJU Int 2008;101:100.

. Novak TE, Lakshmanan Y, Frimberger D. et al. Polyps in the exstrophic bladder. A cause for concern? J Urol 2005;174:1522.

. Toguri AG, Churchill BM, Schillinger JF, et al. Continence in cases of bladder exstrophy. J Urol 1987;119:538.

. Gearhart JP. Failed bladder exstrophy closure: evaluation and management. Urol Clin North Am 1991;18:687.